By Tanu Gago

We say there is no one idea of what a man is - that the notion itself is so broad it makes the task of trying to be definitive seem almost pointless. In Aotearoa, there appears to be a range of factors and complex nuances that impact what it means to be a man. Despite that, one overarching ideal continues to dominate the narrative.

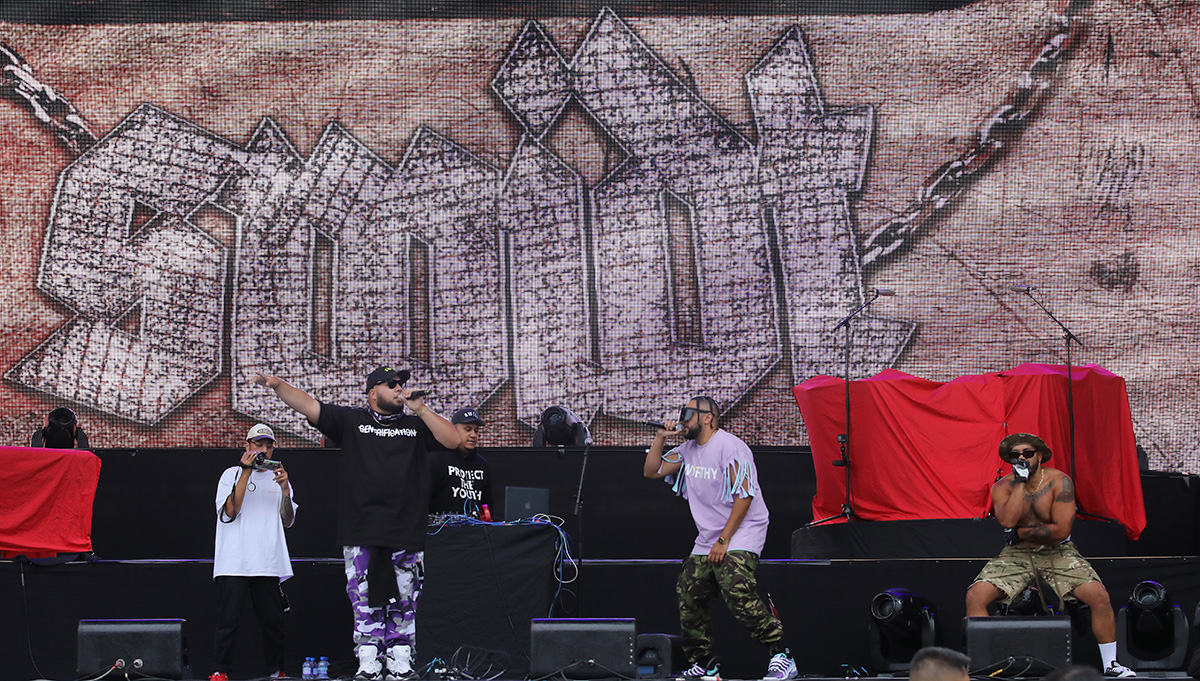

“Tough like an armour truck, the only medicine I know, harden up!!”

The line is from SWIDT’s No Emotions In The Wild and epitomises the version of masculinity which has existed throughout my life. As a Pacific man, it’s easy to feel a deep paralysis when it comes to emotional and mental health issues. We come from a culture groomed through colonisation to be uncomfortable with the soft edges of our identities. From a young age, that premise is reinforced through what we’re praised for, the conversations our families have and ultimately the men chosen as role models in our community. As a result, there’s an internalised fear around being branded weak or inadequate.

For me a heightened period of performative masculinity was attending an all-boys high school in the 90’s. I remember feeling exhausted on a daily basis for having to demonstrate an unnatural amount of physical strength. I liked to draw and this skill always got a pass from the boys. I found that art became my mask and helped me to avoid the boring daily demonstrations of bravado. Not that I couldn't be or demonstrate those things, but more that I didn’t want to.

I grew up in a single parent family with my mum and nine sisters, with two brothers, one older and the other younger. Aside from my brothers there was very little male intervention in my household. It was apparent to me that the need to be seen as strong all the time was learnt behaviour my male peers most likely adopted from the other men in their families.

No Emotions in the Wild is a direct challenge to that. It grapples with the impacts of upholding a one dimensional version of masculinity. It's a scenario fraught with deflated self-esteem and internal conflicts that contradict our desires and abilities for coping as men. Importantly, it’s my first memorable experience in years with the kind of visceral Pacific storytelling that resonates with relatable vulnerability. It’s been a minute since artists have been able to succinctly vocalise the conditions that a lot of Moana Oceania men are confronted by in today's hyper connected world.

For too long, we’ve been bombarded with social and familial expectations to win at life, and to do this by exercising control over all aspects of life. The mental image of a man in control remains one of the cornerstones of modern masculinity. It is in all our cultural languages.

No Emotions in the Wild flexes a vocabulary for vulnerability that is becoming more common in our social toolkit. It uses language that removes many of the social stigmas around mental health. It lets us know what triggers anxiety and social discomfort, helps to identify what people perceive as toxic, and helps to orientate through different emotional moods; normalising the ability to speak openly about mental health issues. It’s a language that someone like me, a gay Sāmoan man who grew up in South Auckland in the 90’s, is only newly accustomed to.

I remember a time when mental health issues were whispered about in private, typically amongst people you trusted and usually with insufferable amounts of shame and self-loathing. There was a time when attitudes towards depression meant family treated you like an attention seeker, and as if your feelings are a coming-of-age phase you will eventually snap out of.

No Emotions in the Wild also demonstrates how some of these attitudes in a Pacific context have passed across the generational gap. It tells us we’re still navigating unhelpful and harmful attitudes, and that has an ongoing impact on how men behave and perceive themselves today.

Photo courtesy of FAFSWAG/Hohua Ropate Kurene and Tapuaki Helu

Even more interesting is how far things have progressed towards openness. Now, it’s not uncommon to be at a party and overhear a casual discussion about different states of emotional survival - whether it’s coping with the modern pressures of study or dealing with the PTSD of a stressful job. Yes, more discussion and information is a good thing. However, we risk minimising the effectiveness of that progress if we’re not genuine about it.

At times, it’s as if the sheer level of awareness and discussion around mental and emotional health and distress has actually deflated the issues. It’s like knowing you’re depressed but remaining very un-bothered because apparently that’s just the norms for everyone. Now post a selfie that captures those feels.

Even emotional distress can be summarised through a string of emojis - with the mini icons punctuating some ironically glib statements about our current emotional state. Problematically, this same colloquial banter seems to permeate through our cultural conversations about masculinity.

We say men are allowed to have emotional range but contradict this by the types of men we construct for our culture to look at. If we canvas the media landscape for an example, we’ll find a very simple image of how to dad; how to be a white man and not an ethnic man; a straight man and not a queer or trans man; how to be a man oblivious of his privilege; an obedient man who does as he is expected; and how to perform our strength, authority and sexuality. We can even find social groups mansplaining masculinity for an entire generation of boys.

I guess that’s why No Emotions In The Wild stands out to me as an important cultural product. It unapologetically points out how dominant Pākehā notions of masculinity are perpetuated and upheld through mainstream culture.

Related to that is a rising call to action amongst young Pacific men who have, in the last few years, mobilised this talanoa into the mainstream discourse. Aotearoa still has some of the highest rates of suicide amongst Pacific men in the world. We know anecdotally there is a correlation between men's mental health and our ability as a culture to show empathy and build healthy expectations of men. However not all men agree with these sentiments. You can still feel the resistance from some men to protect and uphold Pākehā traditions of masculinity.

Photo courtesy of FAFSWAG/Hohua Ropate Kurene and Tapuaki Helu

The challenge is more than simply pivoting and adopting a different position or point of view. This is one part of it, but It has more to do with accountability and being able to recognise the collective responsibility as a community to shift toward more openness. As a collective we have the means to dissolve the narrative that courage and bravery are the only tools available to us. It is also worth remembering our connectedness is amplified in today's modern world; that while we might feel alone, there are resources available to help us mitigate this. For all our brotherhood posturing and rhetoric, there has to be space for vulnerability. There has to be space in our relationships to break down our fears of being real with one another and with ourselves.

There are very real implications to our cultural inability to change. In Aotearoa our ideation for self harm, isolation and instability is a symptom of our unwellness. Some would say this requires radical change but sometimes the most effective change is personal and incremental. Can we just start with becoming more comfortable with our soft edges? Can we start with creating better images of ourselves to look at and look up to? Can we start with reclaiming the stories about who we are away from who we are allowed to be?

It’s pretty obvious to me that we can no longer allow our conscious sightlines to be hypnotised with shallow representations of dumb, sexist, volatile, cliche’s of men in constant control and absolute authority over their environment, their careers, and their bitches. To be honest, it still feels like we are in a first responder state attempting to triage what masculinity means in Aotearoa. But recognising the collective work happening within the culture is pretty hopeful.

Tanu Gago is an interdisciplinary artist and co-founder of Pacific Arts Collective FAFSWAG. He is also the producer of the FAFSWAG podcast MATALA. Created by Hohua Ropate Kurene and Tapuaki Helu, MATALA is a series of conversations and audio essays that places an indigenous lens on the talanoa about masculinity. It is due to be released later this year.

One For The Boys is a documentary, article and photo series about masculinity in Aotearoa today. We look at what it means to be a man, and how and why that’s changing. See here for more from One For The Boys.

Made with the support of NZ on Air.

Where to get help:

- 1737: The nationwide, 24/7 mental health support line. Call or text 1737 to speak to a trained counsellor.

- Suicide Crisis Line: Free call 0508 TAUTOKO or 0508 828 865. Nationwide 24/7 support line operated by experienced counsellors with advanced suicide prevention training.

- Youthline: Free call 0800 376 633, free text 234. Nationwide service focused on supporting young people.

- OUTLine NZ: Freephone 0800 OUTLINE (0800 688 5463). National service that helps LGBTIQ+ New Zealanders access support, information and a sense of community.

Related stories:

Men aren't talking about their feelings and it's a deadly problem | One For The Boys | Ep 3

Men tell us where they feel most and least masculine

Inside the barbershop giving men a place to open up