Non-consensual surgeries on intersex children are still legal. Trans people still struggle to change the sex on their birth certificate. And blood donation criteria still discriminate against gay men.

There’s a lot to celebrate when it comes to rainbow rights in New Zealand. We were the first country in the Asia-Pacific region to legalise same-sex marriage. Our parliament is currently the queerest in the world. And our country specifically grants asylum seekers refugee status if their gender or sexuality makes them unsafe in their home country.

But rainbow communities are still fighting for the right to be treated equally.

Here is an in-depth look at five laws and regulations that still discriminate, or fail to protect rainbow communities. With one in five rainbow youth attempting suicide in New Zealand, changing these laws could be life-saving.

1: Trans and non-binary people still struggle to change the gender on their birth certificate

In 2018, Counting Ourselves - a community-led survey for trans and non-binary people in Aotearoa - found that 83 percent of participants had the incorrect gender listed on their birth certificate.

“It’s really frustrating,” says executive director of RainbowYOUTH Frances Ans. “It's such a basic human right to have documentation that reflects who you are. There should not be so many barriers.”

The process for changing the gender on your birth certificate in New Zealand is still long, exhaustive, and discriminatory.

At the moment, if a trans or non-binary person wants to change the gender on their birth certificate they have to apply through the Family Court and prove they have had irreversible medical changes to conform to their nominated gender.

You don’t need to have had every gender-affirming surgery available to be successful. Community Law's website also states people who have not had surgery, but have been on hormone replacement therapy for a "very long time" have also been successful. But as the current legislation stands medical proof that meets the court's standard of "irreversible medical changes" to "conform" to the nominated gender is still an important part of the application.

Why is this an issue?

This law fails to recognise that surgery is not appropriate or wanted by every trans person. Or if it is, getting access can be incredibly difficult.

Frances Ans Executive Director of RainbowYOUTH

Frances says access to gender-affirming surgery is one of the biggest issues trans people face in New Zealand.

RainbowYOUTH is a charitable organisation that provides support and resources for the LGBTQI+ youth community, and Frances says young people come to them for support constantly because they can’t access this health care.

“The whole space is really fraught,” she says. “It’s completely up to each DHB to decide what kind of access they provide, which means access particularly outside of Auckland is severely limited. Even access here in Auckland is limited. Young people come to us anxious and frustrated, looking for help.”

In mid-2020, around 200 people were reportedly waiting for gender-affirming surgery, which puts the wait time at around 12 years. In 2018, that wait was 50 years.

Previously, the government only funded three male-to-female surgeries and one female-to-male every two years. But in 2018, the Labour-led government abolished this cap and made those surgeries the minimum number of surgeries each year.

The 2019 Budget allocated $3 million to the Gender Affirming (genital) Surgery Services fund over three years - which translates to approximately 13 to 15 surgeries per year.

While trans communities see this as progress, the wait for what is often seen as a life-saving surgery is still too long. Especially because only one surgeon in New Zealand performs these surgeries.

Should trans people have to wait more than a decade to have their birth certificate reflect who they are?

In 2017, a review of the Births, Deaths, Marriages Act led by then-Internal Affairs Minister Peter Dunne was presented to parliament. One amendment to this Act was to make it easier for trans and non-binary people to self-identify.

The new bill would:

- Allow people to specify if they want to be registered as male, female, intersex, or X. At the moment, ‘M’ (male) and ‘F’ (female) are the only two options available to choose from. ‘I’ (indeterminate - neither female nor male) can only be listed if your doctor recorded your sex as this when you were born.

- A court hearing or medical evidence would no longer be required in the application. All you would need to do is swear a statutory declaration saying you intend to continue to identify as a person of the nominated sex and understand the consequences of the application.

But in 2019 the progress of the bill was postponed by then-Internal Affairs Minister, NZ First MP Tracey Martin, and it hasn’t been picked up since.

Update: on August 11 2021 the bill was picked up again and passed its second reading in Parliament, with the support of both National and Labour. It will now go back to Select Committee, which means it can be debated again and will be open to public submissions, both for and against it.

Why did it get postponed in the first place?

At the time in 2019, Tracey Martin said in a statement that she deferred the amendments because "significant changes" had been made to the bill regarding gender self-identification which had occurred "without adequate public consultation".

The Bill faced strong disapproval from conservative, religious and some trans-exclusionary feminist groups. One such opponent of the bill, anti-trans lobby group Speak Up For Women, applauded the deferral of the Bill because they felt the changes to self-identification laws could make cisgendered women unsafe, and because they felt there had not been enough consultation.

Bob McCoskrie, the national director of the conservative lobby group Family First NZ also welcomed the deferral because he believed the proposed bill would make birth certificates “a political tool to further unscientific gender ideology.”

Rainbow communities and allies were upset and frustrated by this move, and believe it only happened because of pressure from conservative groups.

Laura Rapira O'Connell, then-director of ActionStation, an NGO who campaigns for change, said at the time further consultation wasn’t needed because the Human Rights Commission, many LGBTQIA+ groups, and the Privacy Commissioner already supported the changes.

"We don't need consultation with non-trans people on what trans people need. We just need to listen to what trans people tell us they need," she said.

The Act is particularly troubling when it comes to the rights of trans prisoners. Trans prisoners can only be placed in a prison of their identified gender if their birth certificate has been amended.

Given how hard it is to get a changed birth certificate, it’s likely that trans prisoners are being placed in prisons that do not match their gender.

Watch more stories like this: A gender-neutral option has finally been added to NZ voting papers

2: Non-consensual surgeries on intersex children are still legal

An intersex person is anyone born with chromosomes, hormones, or sexual or reproductive anatomy that does not fit the binary definitions of “female” or “male” bodies.

In other words, a child can be born with traits or variations that make it hard for a doctor to tell if they are a boy or girl because they are both, or neither. For example, a child might have external female genitals, but instead of a uterus, they have internal testes.

It is common practice for intersex people to have so-called “normalising surgeries” when they are a child, or sometimes later into adulthood. The main objective of these surgeries is to make the patient’s body better fit the normative and socially-accepted definition of male or female bodies, for example, removing testes from a female-presenting body.

But recently these surgeries on children have been heavily criticised after growing evidence intersex people are left with severe psychological distress and physical complications. There is also the risk that an intersex person could be assigned a gender they later do not identify with.

Dr Rogena Sterling researches the rights of intersex people and is the co-chairperson of Intersex Trust Aotearoa New Zealand

Dr. Rogena Sterling was born with an intersex condition called hypospadias, where the opening of the urethra doesn't come to the end of the penis. They had their first “normalising” surgery when they were just four years old, then another at 15. Like many surgeries on intersex people, it was not medically necessary, meaning the surgery didn’t improve physical health, and Rogena didn’t get to chose.

“The surgery was just so that I could stand up when I peed, like a man,” says Rogena. “But I was never given the chance to know about the physical and psychological impacts of the surgery and decide for myself.”

Rogena has published academic articles on the rights of intersex people and is now the co-chairperson of Intersex Trust Aotearoa New Zealand. They believe normalising surgeries on children, who are not old enough to give consent, take away the bodily autonomy of intersex people who should have the right to chose what happens to their body.

While doctors need the consent of parents to operate on any child under the age of 16, Rogena believes doctors and parents should delay the surgery until the child is informed and old enough to make their own decision.

In 2020, the Crimes Act was amended to make Female Genital Mutilation - the cutting of female genitals for no medical reason - illegal. But the Asia Pacific Forum of National Human Rights Institutions says the laws and policies that prohibit female genital mutilation in New Zealand may actually give explicit permission for genital surgeries to “normalise” the bodies of intersex infants and children. But how?

In the Act, it states that any medical or surgical procedure (including sexual reassignment surgery) can be performed if it is “for the benefit of that person’s physical or mental health.” Influential research from the 1950s on sex assignment argues that having ambiguous genitalia can cause mental distress, so doctors can argue the child is better off being assigned a gender, and they should be operated on when they are young for the best results.

It is difficult to know how many intersex people have had normalising surgeries, as there are no specific records for intersex patients.

A Ministry of Health spokesperson refrained from commenting on whether there needed to be law reform to criminalise surgeries on intersex children who can not give consent. However, they did state the Ministry created new guidelines for the treatment of intersex patients last year.

The MOH spokesperson said “assigning sex at birth used to be done routinely where there is clinical uncertainty but this is no longer the accepted approach.”

“The guidelines, which set the expected standard for medical practitioners, state that non-emergency surgery to determine sex should not be performed at birth.”

While the MOH states these surgeries on intersex children are no longer the “accepted” approach, Rogena says the way the Crimes Act is written means health professionals can legally still perform these surgeries and justify them as necessary for the child's health and well-being, “despite evidence indicating many potential physical and psychological harms.”

For Rogena the answer is clear: “Surgeries should only ever be done if and when the child consents.”

3: It is still a lot harder for gay and bisexual men to donate blood

Gay and bisexual men are required to completely abstain from anal and oral sex for three months if they want to donate blood in New Zealand, even if they have a long-term partner, even if they use a condom.

Previously, the deferral period used to be 12 months, but December 2020 it was reduced to three.

The New Zealand Blood Service says the three-month period allows enough time for HIV to be detected in the sample.

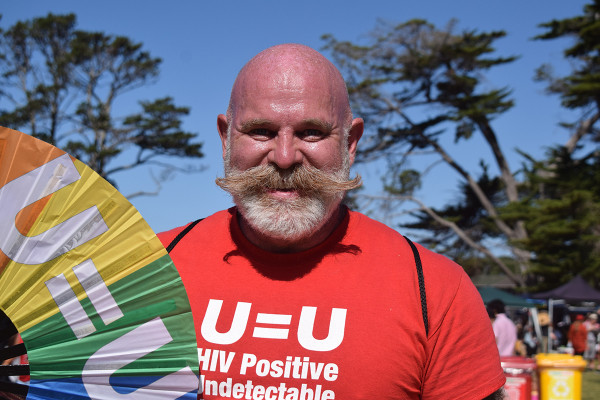

Mark Fisher the director of Body Positive says blood donation criteria is discriminatory

Mark Fisher, director of Body Positive, a support service for HIV+ people, says the change is progress but criteria that specifically target gay and bisexual from donating blood is “still discriminatory because it’s tagging HIV as being a gay disease.”

Restrictions for gay and bisexual men donating blood were imposed by many countries during the height of the HIV/AIDS epidemic in the 1980s. While gay and bisexual men continue to be the most affected by HIV in NZ, heterosexual men and women are not immune.

In 2018, 178 people were diagnosed with HIV in New Zealand. Of these, 111 were men who had sex with men. A further 27 people were infected through heterosexual contact (18 men and 9 women). And the remainder were reported to be intravenous drug use (1), an infant born with HIV (1), and unknown reasons (38).

See more: Women in NZ are getting HIV, but aren’t getting tested

Despite women and straight men also being at risk of HIV, they are only restricted from donating blood on the grounds of HIV risk if they have visited or have a partner from a high-risk country or are a sex worker.

“What it boils down to is trust,” says Mark. “At the moment, what they're doing is not trusting the gay person to say that I am in a stable, monogamous relationship where there is no risk of HIV. Whereas with a straight person, they don't even ask that question. And even if [a straight person] has many casual partners, they don’t care.”

“It's discriminatory,” he says. “We need to move to the assessment of individualised risk, and we'll actually get a safer blood supply by doing that.”

What is an assessment of individualised risk?

Assessment of individualised risk means that every blood donor (regardless of gender and sexual orientation) will be screened for HIV risk in exactly the same way.

- Donors who have had anal sex with a new partner or multiple partners in the last three months would be deferred, regardless of their gender or their partner’s gender. This is because anal sex is riskier than vaginal or oral sex for getting or transmitting HIV because the cells in the rectum are much more susceptible to HIV and both semen and rectal mucosa (the lining of the anus) carry more HIV than vaginal fluid.

- All people who have had oral-only sex would be able donate and would not be deferred

- Donors who have had new or multiple partners recently would be asked if they’ve had anal sex in the last three months regardless of condom use

In essence, the approach will defer people due to high-risk behaviour, rather than because of their gender or sexuality.

The FAIR (For the Assessment of Individualised Risk) research group in the UK have been studying the safety of this approach. They recently concluded donors who had the same sexual partner in the last three months and who do not have an STI should be eligible to donate, and this includes gay and bisexual men.

As a result, the National Health System (NHS) in the UK has committed to implementing these changes by mid 2021.

Dr. Peter Flanagan, transfusion medicine specialist for the NZ Blood Service (NZBS) told Re: the organisation is “supportive” of a move to an individual risk-based approach here in New Zealand, but they need more evidence before they introduce it.

“NZBS is part of a multi-agency research team led by Dr. Peter Saxton from the University of Auckland and supported by the Health Research Council, that is investigating possible approaches to support an individual risk-based approach in this area.”

So while it’s on the cards, it may take a while for it to be approved by Medsafe, the medical regulatory body in New Zealand, says Dr. Flanagan.

4: It is still legal to try and force a queer person to change their sexuality or gender identity

Recently conversion therapy - any physical or psychological practice used to try and change someone’s sexual orientation or gender identity - has gained a lot of traction.

This month, a Green Party petition to urgently ban the practice gained over 150,000 signatures in just one week. As a result, the government has committed to fast-tracking legislation that will ban the harmful practice, with a ban expected to be passed into law by February 2022 at the latest.

See more: Surviving conversion therapy as a young, Māori, takatāpui, autistic person.

While the government has made this commitment, co-founder of End Conversion Therapy in New Zealand Shaneel Lal says the government’s slowness to act is “inherently homophobic”.

Shaneel Lal is the co-founder of End Conversion Therapy in New Zealand

“I don't believe that politicians are intentionally homophobic,” Shaneel told Re:. “But the reluctance to change homophobic laws makes them complicit.”

Shaneel says the Christchurch mosque attacks and Covid-19 have highlighted the government can act fast if they want to. “So when it comes to conversion therapy, why do we have to wait four years, when they have the absolute power to change the law now.”

“It’s a shame and we should not be proud that it will take us another year to ban conversion therapy.”

See more: Joan was tortured for being gay and she is not alone

5: Trans people are not explicitly protected against discrimination in the Human Rights Act

As it currently stands, the Human Rights Act 1993 (HRA) does not explicitly prohibit discrimination on the basis of “gender identity.”

So what does this mean?

Currently, the Human Rights Act sets out several things a person can not be discriminated against. For example, if you were hiring a new employee, you can’t discriminate against their sex, sexual orientation, religion, disability, political views, race, age, marital status, ethical belief, employment status, or family status.

But what isn’t mentioned is gender identity.

This means a landlord could kick a trans person out of their house, just because they were trans, and there would be no protection against this under the Human Rights Act.

It would be a breach of the Human Rights Act to evict someone because they are female, or lesbian - but it doesn’t state that how someone identifies their gender (eg. a trans man) is grounds for discrimination.

Why does gender identity need to be explicitly mentioned in the Act?

To date, no New Zealand court has had to directly consider whether ‘sex’, which is already included in the Act, can cover gender identity. Some international case law concluded sex is synonymous with gender, while other courts have said the opposite.

A Human Rights Commission report found 1 in 10 discrimination complaints relating to sex in the last decade were from trans, intersex, and gender diverse people. This is why rainbow communities want there to be an explicit mention of gender identity to protect their rights. Otherwise, a court case on discrimination could rely on the judge’s perception of what ‘sex’ includes.

Is New Zealand trying to change this Act?

Back in 2004, New Zealand’s first openly transgender MP Georgina Beyer proposed a bill to include “gender identity” as one of the prohibited grounds of discrimination in the Human Rights Act. But it didn’t get past the first reading.

Watch more: The world’s first trans MP: Georgina Beyer

Fast forward to 2019, and New Zealand was specifically called out for its treatment of rainbow communities at a United Nations Universal Periodic Review. Both Iceland and Australia recommended New Zealand add gender identity, gender expression, or sex characteristics as specifically prohibited grounds of discrimination in the Human Rights Act.

Labour’s 2020 election rainbow policies said they want a review of the Human Rights Act to “ensure discrimination on the grounds of gender identity is explicitly prohibited”. Re: reached out to the office of Labour’s rainbow spokesperson Tamati Coffey to get an update on how this review was going, but he did not respond before the publication deadline.

“Trans people need explicit protection from discrimination in the Human Rights Act,” says Shaneel Lal. “We know that they have been denied housing and employment, we know they are subjected to violence. They are one of the most vulnerable groups in Aotearoa - they need explicit protection.”

“We have been marginalised for too long. The government has a mandate to protect queer lives. That needs to happen now. We can’t afford to wait any longer.”

Where to get help:

- 1737: The nationwide, 24/7 mental health support line. Call or text 1737 to speak to a trained counsellor.

- Suicide Crisis Line: Free call 0508 TAUTOKO or 0508 828 865. Nationwide 24/7 support line operated by experienced counsellors with advanced suicide prevention training.

- Youthline: Free call 0800 376 633, free text 234. Nationwide service focused on supporting young people.

- OUTLine NZ: Freephone 0800 OUTLINE (0800 688 5463). National service that helps LGBTIQ+ New Zealanders access support, information and a sense of community.