Content warning: This article contains mention of suicide

I grew up in the pentecostal Christian church from the age of 12 and only properly left at the beginning of 2018. I’m 24 now. Moving around Aotearoa regularly with my whānau, all of the churches I attended taught homosexuality to be a sin.

My understanding of the queer community, my community, grew from the aggressively heteronormative, eurocentric, homophobic, transphobic ideologies I learned in the church. I am a takatāpui person who spent years trying to be straight without success.

It was commonplace for church leaders to lay hands and pray out demons or generational curses (queerness being either of these), as well as less intensely spiritual things too. It was like a dispensement of hope we could always tap into.

While not typical of Sunday services, at youth group it was normal for rings of fire to be held during worship. We’d all line up in two rows facing each other with our hands up and fingertips touching, praying as our peers walked through the rings our bodies formed.

Concentrating a large amount of prayer on someone was thought to create the effect of becoming spiritually drunk or high. It was an intense experience, and common to hear “I’m high on God” or “I’m drunk on the Holy Spirit.”

It was also common for the pastor to pray demons out of the outwardly gay kids. I remember looking on as this was happening one time — this boy was bent over and crying as the pastor screamed for the demons to come out of him. I felt so sorry for him. I knew if I acknowledged I was takatāpui, that would be me, so I stayed right in the closet. It may as well have been my tūpāpaku though.

There were various courses held congregationally and in small groups. Varying in duration, these spanned topics like finances, intentional living, integrity and relationships. Unfortunately the whole time I was in church, no one ever acknowledged that non-binary identities actually existed, let alone were valid.

Image by Trinity Thompson Browne @trin_tb

Homosexuality was sometimes brought up in passing, as a joke in a sermon or within sexuality courses but it was more for the reformed guest preacher to speak on. They usually said things like, “His love will heal your brokenness” (read: your orientation), “It’s a behaviour pattern, no one is born homosexual”, “People who attempt to change their gender are just confused” or rhetoric along those lines.

If you distill down Christianity’s narratives about queerness, the core belief is that queer realities are inherently defective. In Christian teachings we’re taught about our “sin nature” — ourselves pre-converting or being saved. Harking back to Adam and Eve, Adam sinned, Eve followed and the separation of man from God began with sin in all its forms becoming a part of the human experience.

Anything non-straight and non-cisgender is considered to be within the realm of sexual sin. So if I pursue my attractions for those of the same gender, or embrace who I am as a non-cis person, I’m outside of God’s will and choosing to give in to my sin nature at my own peril; hell.

During my decade in church I had three mentors, one during high school and two at university. While beautiful people, we were all products of the Christian doctrine to lesser or greater degrees, and understood sexuality in the same way as the churches we attended — ‘being queer is a defective sexual expression, I will have grace for you and tolerate where you’re at but the end goal will always be for you to become heterosexual.’ My parents didn’t go to church so they never knew any of this went on.

I tried to be straight for the entirety of my adolescence, five of those years in deeply Christian mentor-mentee relationships. What’s more, I pursued those mentorships as much as the church encouraged them because I desperately wanted to be normal; to be truly accepted, not just tolerated.

A lot of my friends now talk about being in relationships in their teens and it brings up a lot of sadness; I never had any of those early relationship experiences. I was convinced all of my attractions to girls were from the devil.

Years went by. I became more and more indoctrinated. Giving everything to be what the church wanted me to be, straight, I never clicked onto the fact that I was being assimilated out of my own internal sense of autonomy in the process. Colonisation of the mind.

When I brought up certain feelings with my mentor, their response would be along the lines of, ‘I’m so sorry you’re feeling like that, and that is valid, but have you considered what you’re experiencing isn’t actually that? This is a consequence of acting on your attraction with that girl last week; you gave the devil a foothold and now Satan is trying to reach further into your life. When was the last time you prayed for forgiveness?’

Always framing a person’s queerness as their own affliction to find relief from through God, this was my normal. For a decade. I’m only now seeing the psychological damage this level of constant gaslighting has done to me and it’s gut-wrenching.

I was taught that loving God would make me straight and fix a fundamental imperfection of who I was — that my queerness was a God given, or God-approved, Satan-imposed cross to bear to strengthen my character. And I believed it with my very breath. But I also begged God to make me straight, that I’d learnt my lesson and he could free me now. I was terrified of going to hell.

People’s souls were objectified constantly in sermons too; people were never themselves in their entirety, they were the personification of a concept — the lost soul, the sinful, the broken, the homosexual — and it was our God-ordained mission to bring them all back to Jesus.

I was always so confused by the language used in church dividing Christians from everyone else. On one hand we were told to love all people, yet on the other, we were in the world but not “of the world”, as if our belief in Jesus somehow imbued our humanity with a layer of spirituality making us superior to everyone else.

We were told to love people, but it was their privilege to receive our God-filled love; it would improve their quality of life because we were in it as a representative of Christ’s love.

I went through two attempts at conversion therapy while in the church — one in high school, one at uni. Did I know it was conversion therapy? No way. It was framed in the terms of being sanctified or purified by Christ through his anointed children.

Within a conversion therapy context, queerness is attributed to anything from intergenerational curses, ancestors who practiced any non-Christian form of spirituality, childhood trauma, neglect, one of your parents not loving you a particular way (yes parents, you heard me), sexual abuse, etc.

Theology is fused with psychology and psychological trauma is equated to sin or a lack of love giving the devil an initial foothold in your life; everything is then linked back to the enemy’s influence over your life.

You’d pray for God’s forgiveness over and over again. If he thought you could handle it, well, nothing would change and it would suck. If you didn’t have any attractions to the same gender that week, you’d thank God for protecting you from Satan.

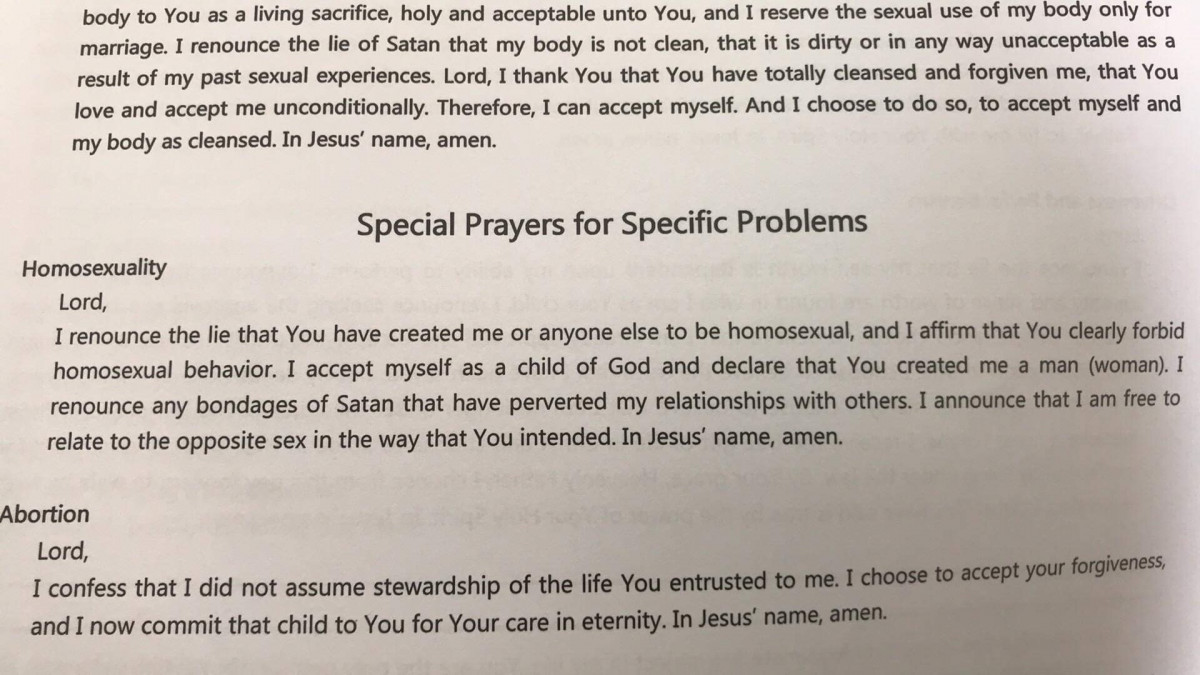

The second attempt of what I’d define as a form of conversion therapy was a 12-week course where the two women running it knew I struggled with same-sex attraction. They made this my focus for the whole 12 weeks.

I wanted to be straight so badly. At the end of the course, we went on a full day retreat at the church centre where the main church leaders prayed with us over our lives and specific things we were struggling with. You know the deal — pray the gay away. The photo below is from that day.

In the Pentecostal churches I went to, they never called it conversion therapy; it was spiritual freedom, spiritual purity, strengthening your relationship with Jesus or equipping you to step into God’s call on your life.

There are contracts, given and signed with the intention to create a physical representation of your commitment to Christ, to the church and to yourself. But these contracts always have a clause waiving your right to hold the church to any liability and clearly stating their ‘guidance’ isn’t therapy.

Conversion therapy more often than not was always implicit. I was going through explicit conversion therapy as a minor and I didnt even know. It’s spine-chilling to think that if I wasn’t takatāpui myself, I’d still be so deeply indoctrinated.

I’m also very aware of how churches treat people who speak up. One time someone spoke out against the church via a newspaper article and I remember the pastor addressing it in the Sunday sermon in front of thousands of people, dismissing them as spiritually blind as a result of leaving the church.

The devil was using this person to discredit the church, he said, we are making movements to expand our reach into different communities and this is the devil pushing back, which means we are on the right track, was his reasoning.

I’m expecting a pushback to sharing my story. I don’t care. I didn’t have anyone to look up to when I was in the church who was young, proudly takatāpui, Māori and autistic so if I can be that for another young person, it’s worth it.

As to why I left the church, it’s like how it is for a lot of takatāpui people — I became suicidal. After nearly a decade in the church, I was at the end of myself trying to become straight; I had nothing left.

I was at the Ngauranga train station one day watching the trains and thinking, “It would be so easy for it all to just be over.” I remember a high pitch whine in my ears and the chant, “ka mate, ka mate, ka ora, ka ora,” from the haka reverberating through my body on repeat. My tīpuna knew I was at the edge.

That day it literally came down to, “do I die or do I live?” I wasn’t ready to die yet and so, leaving the church was the best decision I ever made.

A few months later, I went to the United Nations in New York with a group of rangatahi Māori and I came out for the first time there. It only took a few days to realise how indoctrinated I was.

Five of the ten of us were takatāpui and I remember thinking how utterly ordinary queer people were. They cried like me, they laughed like me, they did washing and danced and got moody like me, they were just so… human? And here I was, 21 years old at the UN figuring all this out.

I want to mihi to all the mates who loved, accepted and celebrated my takatāpuitanga until I was able to do this for myself. I’m stoked to say that I came out to the world in New York City, and that Hayley Kiyoko’s album Expectations was the soundtrack. Given her fan name is Lesbian Jesus, I find this to be satisfyingly iconic.

Fast forward three years, we’re in 2021, I’ve had two relationships with two incredible wāhine and felt heartbreak twice. I’m releasing my first solo track about conversion therapy, baptise me soon, I’m publishing my first poetry and photography book, i am navigator next year and I’m surrounded by loved ones who fill my life with joy.

Looking at my life now, I am so thankful I chose living that day. But so many young people in a similar or more severe position choose to die. I hope my story helps you understand why.

It’s never just conversion therapy as its own medium, it’s all of the aggressive micro and macro-expressions of this harmful, colonised doctrine that go along with it. What would effectively banning conversion therapy look like? I honestly don’t know; for me conversion therapy started the moment I walked into church.

I hope my story brings you the relief of feeling seen and validated in your own experiences, wherever it finds you. And if my experiences aren’t your own, I hope it connects you to a loved one who went through conversion therapy too.

Ki a koutou e huna ana i raro i te kapua pōuriuri, i te kapua pōtangotango, tēnā, kia manawanui mai. Maumaharatia tō tūākiritanga atu i te hāhi, maumaharatia tō ake mana motuhake. Whāia he hūarahi anō mōu, mō tō oranga, mō tō hauora. Kaua e noho ngū kai te mura o te ahiahi, ehara koe i tētahi hapa, ehara hoki koe i tētahi hē. He tāonga koe nō tō tātau nei atua kia poipoia, kia pūāwai i roto i te waonui a Tāne.

Where to get help:

- OUTLine NZ: Freephone 0800 OUTLINE (0800 688 5463). National service that helps LGBTIQ+ New Zealanders access support, information and a sense of community.

- Suicide Crisis Line Free call 0508 TAUTOKO or 0508 828 865. Nationwide 24/7 support line operated by experienced counsellors with advanced suicide prevention training.

- Youthline Free call 0800 376 633, free text 234. Nationwide service focused on supporting young people.

- 1737: The nationwide, 24/7 mental health support line. Call or text 1737 to speak to a trained counsellor.