Sexual diversity and gender fluidity are nothing new in Aotearoa, they’ve always been around.

New Zealand is currently debating whether or not gay conversion therapy should be banned after two petitions calling for an end to the controversial practice were delivered to parliament. The Justice Select Committee have considered the issue and so far decided not to recommend a ban, citing rights relating to freedom of expression and religion.

It’s an issue that young trans woman Falencie Filipo says would never have featured prior to colonisation. Being gender fluid or sexually open has traditionally been accepted in Polynesian communities. The belief that people with diverse sexual orientations or gender identities should be given therapy to make them fit within hetero-normative standards is completely at odds with this history, she says.

Falencie Filipo, 25

Research shows fluid genders and diverse sexualities were common throughout the Pacific before colonisation. But since 1840 when homosexuality was outlawed in New Zealand (it wasn’t legalised until 1986), stigma and shame was inflicted upon queer people, and still is today.

“In high school the boys used to say, ‘have you slept with a woman?’ And I would be like, what the hell, where are all these questions coming from?”

Falencie Filipo is a New Zealand born Samoan who attended a Catholic all-boys secondary school. She says she was ridiculed all the time for being herself.

“The boys would say, you should try it. How can you not like a woman? They would just try to put those thoughts into my head. Which never crossed my mind because all I could think about was how disturbing that is.”

Falencie says she found support amongst other trans or fa’afine at her school too.

“We just stuck with each other and the boys just ostracised us in the corner like ‘oh faggots’ but they’d just leave us there.”

Falencie says she started transitioning at 16 and while it took her family time to get used to it, she still had to get through the pressures at school.

“The boys just wouldn’t stop, they would just pick on you in class. They would just direct the whole narrative towards you and say things like ‘oh miss, he’s a sin because he’s changing his gender’ and they would all start laughing.”

Falencie says although she wanted to cry, she wouldn’t let herself break at school.

“I would just come home and cry.”

Now, Falencie is forging a pathway for other trans youth to be who they truly are.

Originally from Māngere, Falencie works on Auckland’s waterfront for ASB Bank, lives in a CBD apartment and is constantly creating art works and performances with her community.

Falencie Filipo and Jaimie Waititi are both members of diverse arts collective FAFSWAG.

“Trans women need to realise that what we are is enough,” says Falencie.

“It takes time. It may be difficult but you have to go through the tough times first so you can grow as a person. Then you’ll grow and blossom into a stronger woman, with a lot of confidence and just an unapologetic mindset.”

Falancie says, “What we can do is educate our people about our ancestors and our indigenous practices.”

Early evidence shows that homosexuality and gender fluidity was visible in Polynesia when European explorers ventured into the Pacific.

In 1789, British Royal Navy officer William Bligh described a Tahitian ‘māhū’ in his journal entry.

‘These people... are particularly selected when Boys and kept with the Women solely for the carenesses [sic] of the men… The Women treat him as one of their Sex, and he observed every restriction that they do, and is equally respected and esteemed.’

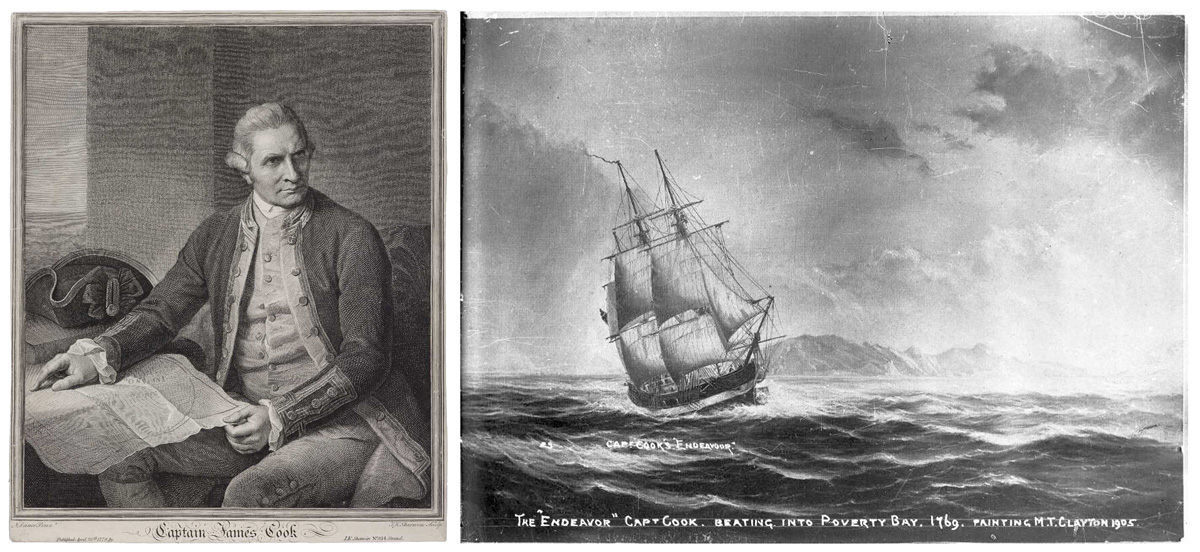

Onboard the Endeavour in 1789, a member of James Cook’s crew wrote about a meeting with non-binary men during an early voyage to New Zealand.

Left: Captain James Cook 1751 - 1790 by Sir Nathaniel Dance-Holland (National Library of New Zealand) Right: The Endeavour ship by Matthew Thomas Clayton (National Library of New Zealand)

‘One of our gentlemen came home to day abusing the Natives most heartily whom he said he had found to be given to the detestable Vice Of Sodomy. He, he said, had been with a family of Indians and paid a price for leave to make his addresses to any one young woman they should pitch upon for him; one was chose as he thought who willingly retird with him but on examination proved to be a boy; that on his returning and complaining another was sent who turned out to be a boy likewise; that on his second complaint he could get no redress but was laught at by the Indians’

Sex between men is also documented in Māori records from this time. A waka huia (treasure box) carved in the late 18th century, which is now held in the British Museum, depicts eight male figures engaged in sex acts.

Waka Huia (treasure box) from the late 18th Century. © The Trustees of the British Museum.

Takatāpui is a traditional Māori word describing a same-sex companion, that has recently returned to common usuage. It now embraces all Māori of diverse genders and sexualities.

In the Pacific, gender identities include fa'afafine (Samoa), fakaleitī or leitī (Tonga), vaka sa lewa lewa (Fiji), fakafifine (Niue), pinapinaaine (Kiribati and Tuvalu) and akava'ine (Cook Islands). Diverse genders are also recognised by indigenous cultures around the world, like the two-spirit people (Native Americans) and hijra (India).

History shows we now have very limited views on how we identify our gender and sexuality. But research is finally underway to recommend how to care for and support our queer or Rainbow communities.

In September 2019, the Counting Ourselves report became the first ever comprehensive survey of the health and well-being of trans and non-binary people in Aotearoa.

The report found more than two thirds of trans and non-binary people had exprienced discrimination at some point - particularly trying to find a job or housing, or when they were at work or in public places.

A third of people surveyed said they had avoided seeing a doctor in the last 12 months out of fear of being disrespected or mistreated.

One recommendation from the report stated trans or non-binary people can be protected from discrimination by being surrounded by a supportive commuinity.

But sometimes, your community can also be to your detriment.

For Te Rata Hikairo, it was his Mormon church community that insisted he get therapy to “help” him with his sexuality.

Te Rata Hikairo, 31

“There’s a strong Mormom background in Te Tai Tokerau where I grew up. And then when I was getting involved in that church at 18-19, I had a kōrero with my bishop, and the congregation paid for me to have sessions with LDS Family Services. All with the view that you were straight.”

LDS Services was established by the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints.

“According to church doctrine, I could never have what they term as an eternal family and be married in the temple. Because the only people who can get married in the temple is a heterosexual couple. And you have to be living in line with the church’s moralistic standards.”

Te Rata says, “it really spun me out and brought me into this horrible anxiety and depression. I had at the time, about ten years ago, self hate, hate of religion and just so much regret about my life.”

A decade on, the attitude of the Church has changed. Director of government and community relations, Marty Stephens says, “the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints opposes ‘conversion therapy’ and our therapists do not practice it.”

An official church statement says, “The Church hopes that those who experience same-sex attraction and gender dysphoria find compassion and understanding from family members, Church leaders and members, and professional counsellors. The Church denounces any abusive professional practice or treatment.”

But while there may the Mormon church have moved on from gay conversion therapy, it is still legally practiced in New Zealand, particularly by churches. The Justice Select Committee published a report this October declaring more work needs to be done before any decision is taken to ban it. “In particular, thought must be given to how to define conversion therapy, who the ban would apply to, and how to ensure that rights relating to freedom of expression and religion were maintained.”

Reverend Vicar Helen Jacobi from St Matthews Anglican Church in Auckland City says the problem is that different churches keep to themselves.

St Matthews-in-the city Church on Nelson St, Auckland City.

Reverend Jacobi says, “Those of us who would ban it and not want it are not in conversation with those who are those who are implementing it.”

She says it would be hard to get church leaders together from different denominations, “because we operate in different circles.”

Reverend Jacobi says St Matthews-in-the-city has supported the city’s LGBTQIA+ community for decades, with the Auckland Rainbow Community Church.

“That’s been a strong part of our story and our history.” she says.

The church is independent, growing out of a bible studies support group for gay men that started 40 years ago.

Reverend Jacobi says, she’s puzzled as to why the Government won’t ban conversion therapy.

“I’m quite surprised the Government hasn’t been a bit stronger on banning it.”

Te Rata expects it will take more than two petitions supported by 20,000 signatures to lead to change.

He says,“I know that if you actually want to achieve a ban you have to talk kanohi ki te kanohi (face to face).”

“We’ve got to work with them (church leaders) to have them understand that they do have mana and they do have the right to teach their faith but we have to be careful that we do not isolate youth.”

This article is a part of Rediscovering Aotearoa: a decolonisation series. Watch our short documentary on Takatāpui/LGBTQIA+ here and listen to our podcast here.

Made with support from NZ on Air.