I just got out of prison and have to rebuild my life with $350

If you were getting out of prison and trying to get your life back together, how long would $350 last?

For people being released from prison in Aotearoa, the main support is a $350 payment - but that amount has stayed the same since 1991 - while inflation and the cost of living have all gone up.

Advocates say it’s not enough and believe a lack of support is a big factor that contributes to prisoners reoffending.

Here in New Zealand, over a third of people who leave prison are back inside within two years.

Anna Harcourt spoke to two former prisoners about their experiences of rebuilding their lives after prison, investigating what support there is for them.

DAY 1: RELEASE

It was the first time he'd seen the sun for three months.

Joao (32) says, “You don't hear birds. You don't hear wind, you don't hear sounds of water. All that is quite noticeable when you get out [of prison].”

Joao has been in and out of prison so many times he’s genuinely lost count, but this time he hopes he can stay out. Photo: Re: News

Joao was handed back the clothes he was arrested in, but says they’d just sat in a bag with his shoes for three months - unwashed. (Corrections dispute this and say they wash all clothes.)

He walked out the Auckland Prison gate in Paremoremo still wearing his prison shorts, and a white t-shirt his mum had brought for him.

He hadn't had a shave or a haircut in a long time and felt anxious and insecure about his appearance. He was both excited and really worried about his release.

“You just don’t want to go back [to prison].”

In New Zealand, over a third of people who leave prison go back within two years.

Joao says, “Once you go in, it's very easy to go back, and it's very hard to get out.”

Joao’s mum picked him up and drove him to the airport so he could fly to a rehab clinic in Wellington where he’d spend four weeks.

DAY 2: REHAB

Joao spent most of his twenties in and out of prison - so many times that he’s genuinely lost count, mostly on meth-related charges.

He’s been addicted to drugs since he was 15, and has been to rehab in the past, but this time he was determined.

Whilst in prison he contacted a drug and alcohol rehab and a judge granted him bail to leave prison to attend Red Door Recovery.

“I'm grateful for the judge to give me that chance,” he says, “because I do want to change.”

At Red Door he met 30-year-old Brendan who got out of prison seven weeks before him. Brendan is also on electronic monitoring bail whilst he tries to overcome his meth addiction.

Ex-prisoner Brendan says his offending has been driven by his meth addiction. Photo: Re: News

He’s also grateful to be at Red Door—the last time he got out of prison in 2022 he was back on meth within six hours.

“Getting out of prison and not having a programme to go straight into or any structure can be a really scary, daunting, and difficult process.”

Brendan says after being in a cell, he’s thankful just to be able to walk out onto the lawn on a sunny day at Red Door.

Red Door Recovery was founded by David Collinge after his own son struggled to access meth addiction services. Photo: Re: News

“I mean, some of the things that we've been doing since coming here are just things I haven't done since I was a kid, you know, go-karting, going out for fish and chips on a sunny day, having some authentic laughs with people. It's a really nice change in pace for me in comparison to what I've been experiencing the last ten years since I've been caught up in my addiction.”

Nearly 40% of prisoners in New Zealand have abused or been addicted to methamphetamine, according to a 2015 study. And over half of all drug charges are now for meth.

Brendan has been to prison multiple times for theft and fraud, but says it’s all been related to drug relapses, “I've got a quiet determination this time.”

Red Door is a private rehab run by David Collinge, who started it after his own son became addicted to meth and was in and out of prison.

It’s not easy to get a place at rehab, David says, and across the country demand outweighs supply.

The waitlist at Red Door is about six weeks, but he knows of rehabs where it’s more like six months.

“There’s a moment when we elect to turn our lives around and you want to move as quickly as you possibly can. And the wait times are getting ridiculous, especially since meth is making its impact.”

Getting help isn’t cheap - David says Red Door costs about $8000 a month, but other private rehabs can cost as much as $30,000 a month.

Joao’s mum and grandma are paying privately for him to be here. “Without them, I actually don't know where I would be,” he says.

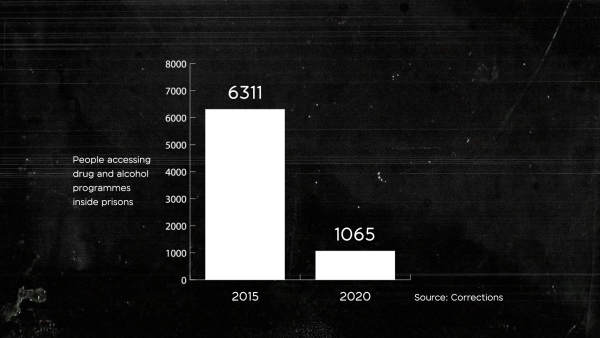

Corrections run alcohol and drug programmes inside prisons, but the number of people accessing them has dropped significantly— from over 6000 people in 2015 to 1065 in 2020.

The number of people accessing drug and alcohol programmes inside prisons has dropped significantly since 2015. Source: Re: News

They also run a 24/7 helpline, a 12-person rehab in Christchurch, and an aftercare service to support people who have done a drug or alcohol programme while inside prison. But last year, of the 20,000 releases from prison, only 105 people accessed the aftercare service.

Brigid Kean, Deputy National Commissioner at Department of Corrections, says Covid played, “a pretty unfortunate part in that,” and Corrections is trying to improve access through video services.

DAY 3: STEPS TO FREEDOM

The main support for people coming out of prison is a one-off $350 payment from the Ministry of Social Development called Steps to Freedom.

It’s intended to help people make a new start in life by paying for things such as rent in advance, food and household items etc.

Joao bought shoes, some clothes and a haircut. Just like the previous times he got out of prison the money was all gone the same day.

The Steps to Freedom payment hasn’t increased in 32 years.

In the early 90s median rent in NZ was $150 a week. It’s now $560 a week.

Unlike benefits or superannuation, the Steps to Freedom grant isn’t connected to inflation or average wages - so even as the cost of living has gone up, the rate hasn’t.

According to the Reserve Bank’s inflation calculator, $350 in 1991 would be worth $710 today.

$350 in 1991 would be worth $710 today, according to the Reserve Bank’s inflation calculator. Source: Re: News

Aphiphany Forward-Taua, the Executive Director of justice advocacy group JustSpeak, says $350 is nowhere near enough.

Justice advocate Aphiphany Forward-Taua says some ex-prisoners turn back to crime because they can’t survive on the current support offered. Photo: Re: News

“We know that typically it doesn't go any further than the first meal that a person has out of prison, socks, a change of clothes if you're lucky and maybe a night stay in a hostel.”

And former prisoners might not even get the full $350. If they have any money in their prison bank account—the one used to buy things at the canteen, or where wages are paid for work they do at the prison—that amount gets deducted from the $350.

Joao wasn’t handed this money as he walked out the prison door—he needed to make his way to a Work and Income office, which took three days because conditions of his bail meant he couldn’t leave the rehab’s premises without permission from Corrections.

Forward-Taua says JustSpeak has been told of cases where people were released from prison on a Friday afternoon—too late to get to a Work and Income office as they’ve already closed. “So then they basically have a whole entire weekend where they can't get any access to money.”

She says in the worst scenarios this can lead to people turning to crime again.

Ministry of Social Development client service delivery director Jamie Robinson says Steps to Freedom can be paid to a person in prison up to five days before their release and prisoners can apply for it weeks in advance. He added that whilst the Work and Income offices are closed over the weekend, the phone line is open on Saturday until 1pm.

Robinson says, “The Steps to Freedom grant is just one way we can help. We can also consider other benefits and financial assistance.

“We are particularly focussed on supporting them to find sustainable employment so they don’t have to rely on benefit payments.”

In 2019 the government’s Welfare Expert Advisory group recommended an increase to the Steps to Freedom grant but four years later, nothing has changed.

Minister for Social Development Carmel Sepuloni says, as part of its wider welfare overhaul, the government will—in the next one to two years—explore how the Steps to Freedom grant can better support prisoners.

She says the government has expanded support for people leaving prison through an employment scheme, and a targeted Māori Pathways initiative.

Former prisoner Brendan says it’s hard to rebuild your life with only $350.

“It’s almost such a kick in the stomach that you just want to go smoke meth and do crime cos they're really giving you no footing.”

DAY 6: REOFFENDING

“I know many guys that have been out for like six days, nine days,” says Joao, “...and they're back in there.”

He’s not surprised to hear over a third of people who leave prison are back within two years.

“Inside prison if someone annoys you, like if they use your canteen containers when you told them not to,” he says, “you punch them.”

“It's okay and it's what you do, you use your fists otherwise they continue to do it.”

“But when you get out, you can't do that kind of thing. So that's where a lot of guys I know, they get out, and someone's pushed that button and next minute they’re back in trouble with the police.”

That violence changed Joao, and he says prison is where he first learnt to throw a punch.

“If anything, I think that Corrections has damaged me. You know, I've made more poor choices because of my experience that I've had from prison.”

“Up until I went to prison, people didn't have to fear me, and they didn't have to worry about how I'm going to react when in an uncomfortable confrontation or communicating with me. But over the years, that's changed.”

Joao is due to be sentenced later this year after pleading guilty to a number of charges including assault.

Joao says he takes full responsibility for his actions that landed him in prison, “I do regret a lot of decisions that were made in my life.”

The shortest time he was out of prison was three months. “It was my own behaviours and my own flaws that led me to reoffending.”

He doesn’t believe it’s right to just blame the system for his re-offending, “I just think that, you don't grow, you don't mature when you're in prison. Time stays still for you. And you know, it doesn't do any good for anyone that I know when you’re put in prison.”

In 2018 the government pledged to reduce the prison population by 30% over 15 years, and it has dropped significantly, from a peak of 10,600 in 2018 to 8,300 in March this year.

Brigid Kean. Photo: Re: News

Brigid Kean, Deputy National Commissioner at Department of Corrections says, “We're doing a lot, but there's always room for improvement and growth.

“It's not something that we can do alone, but the re-conviction and re-imprisonment rates have actually reduced over the last few years. So I believe that we're heading in the right direction and we're doing everything we can to support people who come into prison with very little and damaged lives to come out better than they were before they came in.”

DAY 14: HOUSING

After a month at Red Door Recovery, Joao graduated from his drug programme. He’s now in their two-year aftercare programme, and as part of that has moved to their housing in Upper Hutt.

“I’m just lucky that they had a room available for me, I'll be taking the last room at this house, because they don't have enough for everyone.”

Getting a house is one of the hardest things for people coming out of prison.

This time two years ago when Joao got out of prison on a previous release he tried to move from Auckland to Wellington, “I went to between 50 and 70 house viewings in a period of about two months. So every night I was going to a house viewing and I just wouldn't get a phone call back.”

He managed to get work as a welder but says even having a job isn’t good enough, “My criminal record screwed that. I suppose if I was a landlord I probably wouldn’t give them a chance either to be honest.”

He thinks it contributes to people re-offending.

“I think they end up being stuck in a rut. They go back to where they last kicked off. It's hard to make new friends or hard to have that commonality with somebody that hasn't had that experience. So you end up grouping, if that makes sense.”

Aphiphany Forward-Taua of JustSpeak says the prison system contributes to a “secondary sentence”.

“It's difficult for them to find housing. It's difficult for them to find employment. And it's also difficult for them to get access to health services like addiction services. That all contributes to re-offending.”

At the beginning of this year the U.S. city of Atlanta introduced a new local law preventing discrimination against people with a criminal record.

This means they can no longer legally be denied things such as housing, employment, or any other goods or services based on their previous convictions.

Forward-Taua wants to see the same thing here in Aotearoa, “It ensures that people coming out of prison are able to engage in our communities and in our society in a meaningful way.”

Brigid Kean, Deputy National Commissioner at Department of Corrections, says most people coming out of prison don’t need the support.

“They have their family, they have their friends, and they have the kind of support networks that they had prior to coming to prison.”

Corrections runs a range of housing and employment support programmes.

But of the 20,000 times someone was released from prison last year, less than 3000 got help from those programmes.

Kean says there's “no doubt” housing is a critical challenge for many people, not just those coming out of prison.

“We do a lot with prisoners to help them get into accommodation when they come out. In the last year or so, we've placed about 1200 people into accommodation.”

She says Corrections have doubled their spend on building accommodation stock.

“But there's no question that housing is a big challenge in New Zealand at the moment and we can't do it alone.”

Research done by Associate Professor of Criminology at the University of Auckland Alice Mills found people leaving prison without stable housing are almost five times more likely to be re-imprisoned.

Mills says housing support for former prisoners is “patchy and inadequate”.

DAY 30: FIGHTING YOUR DEMONS

Without the proper treatment, people who have addictions running through their family for generations can pass the trauma down to their children and children's children.

At Red Door Recovery, Brendan learnt for the first time about the concept of intergenerational trauma. He says it makes “a hell of a lot of sense”.

“Unless there's intervention, rehabilitative intervention, then that's just going to continue that cycle. And it just seems bizarre to me that people aren't doing more to help that, you know?”

He feels “quite blessed” to have learnt what intergenerational trauma is, and hopes when he has children one day, “I'll break that cycle for my family”.

Joao hasn’t yet allowed himself to dream about the future. For now, his focus is on fixing himself and his core issues—depression, anxiety, and addiction.

“My goal at the moment, my hope, is to learn a new way. Just to try and change.”

He’s hoping this time he won’t be one of the 36% of people who go back to prison within two years of getting out.

“I don't want to go back. I don't want to go back to drugs. And I don't want to go back to prison.”

He knows he’s hanging on by the skin of his teeth.

“But there’s definitely hope that I'm going to be alright.”

To get help:

1737: Nationwide 24/7 mental health support line. Call or text 1737 to speak to a trained counsellor.

Alcohol and Drug Helpline: Free 24/7 helpline 0800 787 797

To contact the author of this story email anna@renews.co.nz

*This article has been amended to add more information about Joao’s charges.

More stories:

Re: Investigates is a series of short docos exploring some of the biggest issues in New Zealand today. Watch more here:

How Dunedin became the MDMA capital of NZ

Wastewater testing shows MDMA use has gone up 40% in the last three years in the Southern region.

Inside ram raids: Why NZ teens are crashing cars into shops

Nearly 90% of ram raid offenders are under the age of 20, with the majority under 17.

Her best friend died at a Dunedin flat party. Now she's calling for change

Megan Prentice's best friend Sophia Crestani died in an overcrowded flat party in 2019.