This article was originally published June 5 2020.

Update: As of June 9 2020, it was announced Police would no longer continue Armed Response Teams. Police Commissioner Andrew Coster said it was clear to him "these response teams do not align with the style of policing that New Zealanders expect."

Public feedback and consultation with community groups were key in making the decision to scrap ARTs, as well as preliminary findings from the Police's own assessment.

"I want to reiterate that I am committed to New Zealand Police remaining a generally unarmed Police service," said Commissioner Coster in a media release. "“How the public feels is important - we police with the consent of the public, and that is a privilege."

In October 2019, police in New Zealand began arming officers for a six-month trial. The Armed Response Teams were meant to respond to “significant risks” but instead largely were used for traffic stops. In June 2020 the police asked for public feedback on the trial. The #ArmsDown movement says Aotearoa does not need cops with guns.

The Black Lives Matter protests throughout New Zealand were sparked by police brutality against Black people in the United States, but they were also fuelled by anger at the treatment of Māori, Pacific and other people of colour in Aotearoa.

Many carried banners with the slogan #ArmsDownNZ” - a phrase which has erupted alongside #blacklivesmatter online since the killing of George Floyd last week.

Co-founder of the Arms Down Campaign Emilie Rākete says arming police will ultimately lead to the deaths of Māori and Pacific people. Between 2009 to 2019, two-thirds of all people shot by New Zealand police were Māori or Pacific.

“Look at who is dying - it is overwhelmingly Māori and Pacific people being shot and killed by the police.”

“We know it is going to be Māori people. We know it is going to be people experiencing mental health problems.”

Arms Down co-founder Emilie Rākete

The Arms Down campaign began in October 2019 in response to the announcement that police would be trialling an Armed Response Team (ART) in three New Zealand communities for six months.

As part of this trial, which ended in April 2020, teams of police officers patrolled communities in Canterbury, Waikato and Counties Manukau armed with Glock pistols on their person and Bushman rifles in their vehicles.

The police say these areas were chosen because they have the highest rates of firearms offences. However, critics of the trial pointed out that these areas have disproportionately high numbers of Māori and Pacific residents.

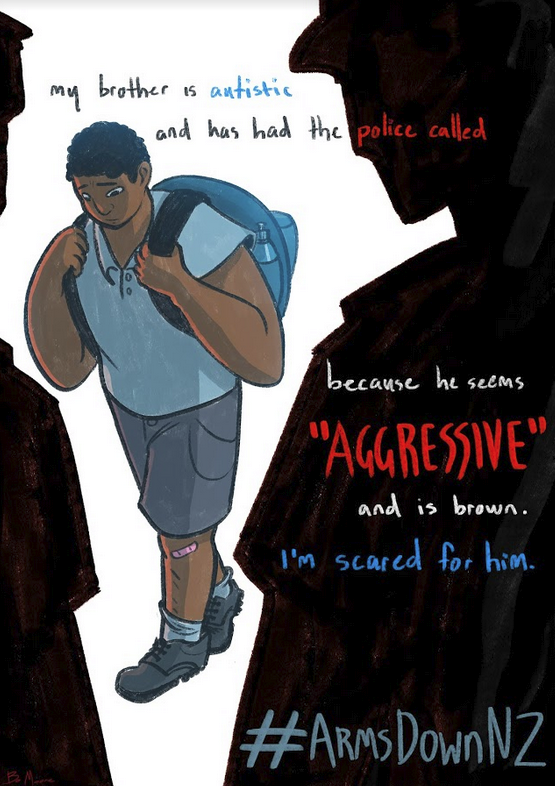

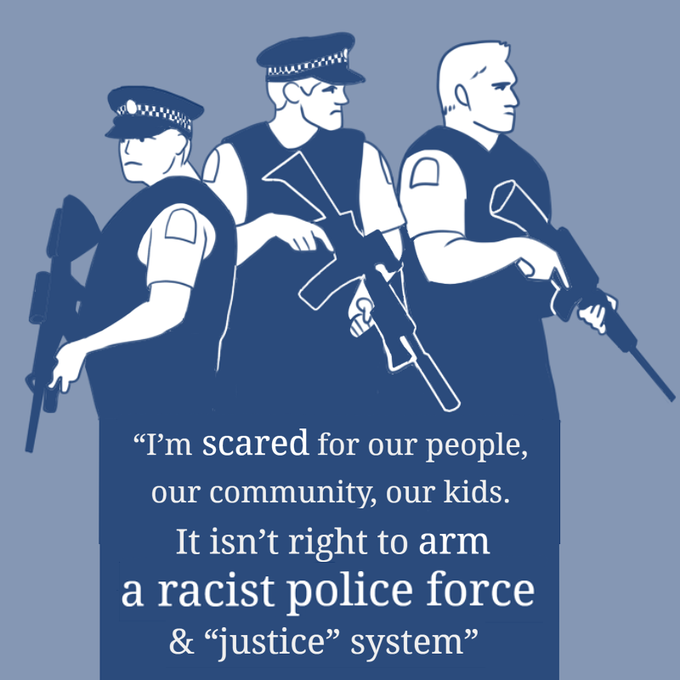

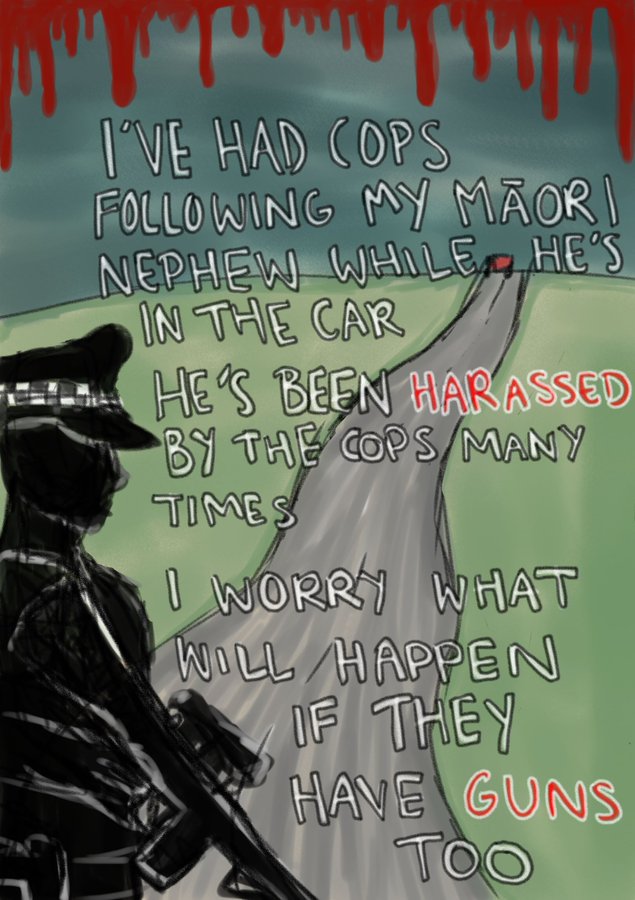

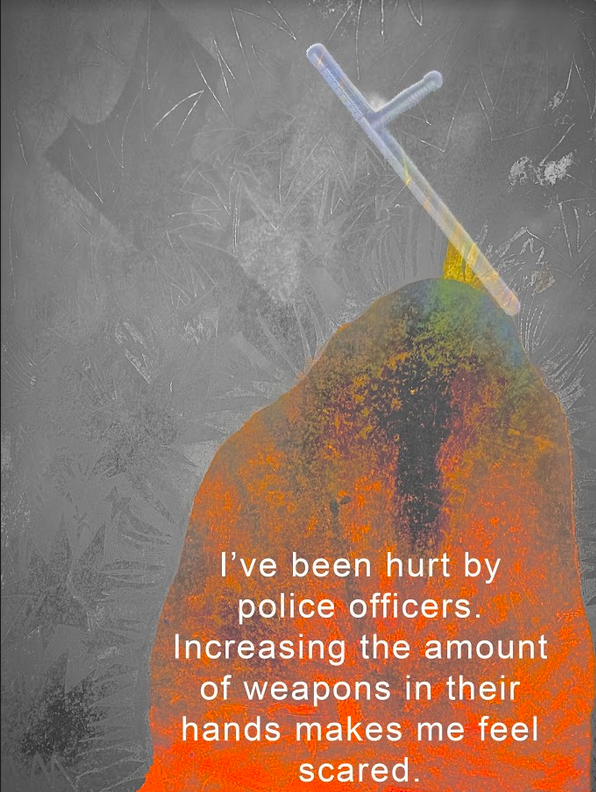

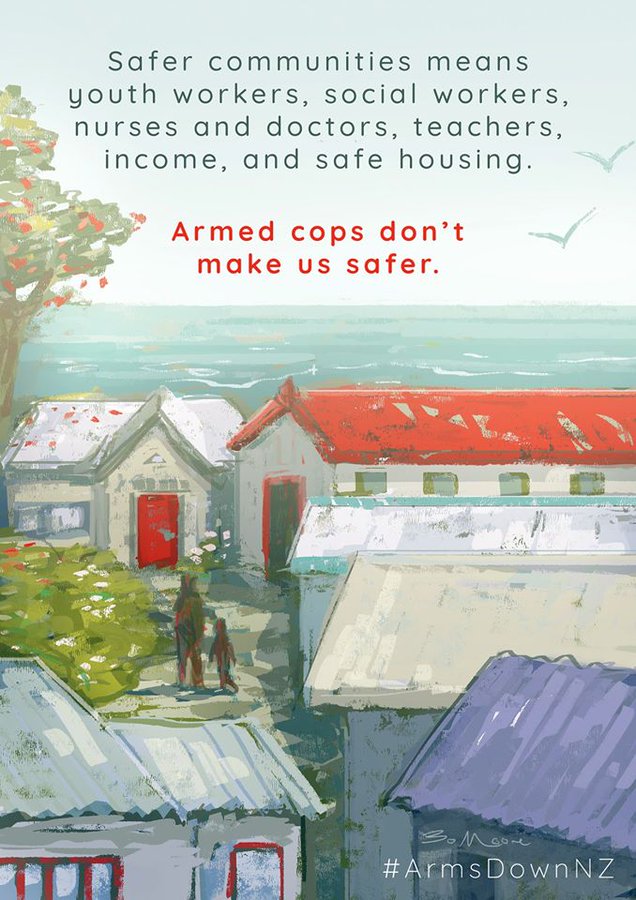

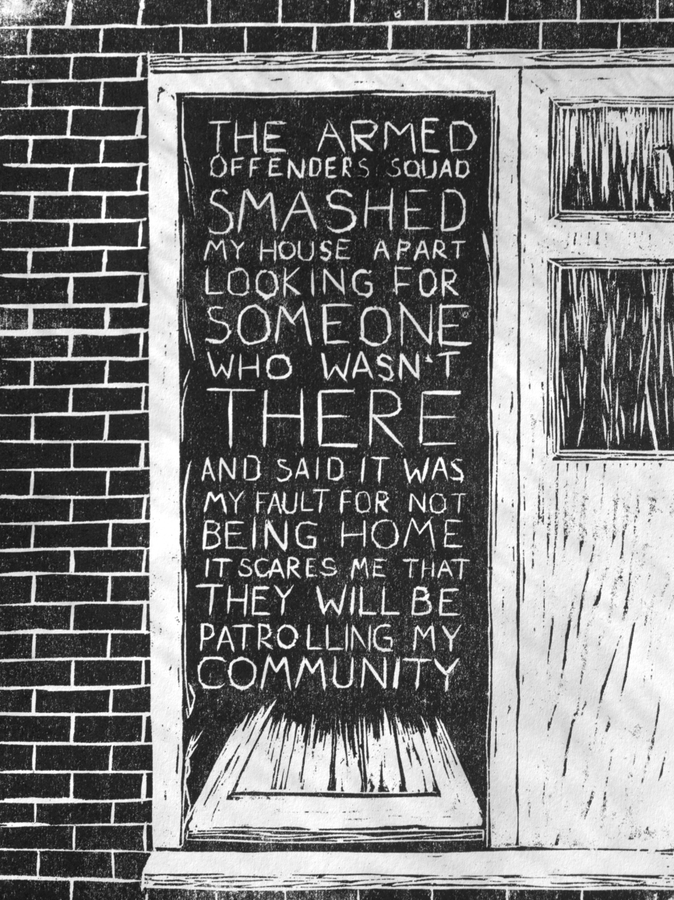

The #ArmsDown campaign have created artworks with quotes of people's experiences with police. Image: @armsdownnz

Police anticipated that this trial would have a negative effect on these communities. Documents obtained through the Official Information Act by The Herald showed researchers evaluating the trial before its launch concluded that it could “further compound already strained relationships with Māori and Pacific communities”.

This strain is created partly by the fact that, per capita, Māori are 7.6 times more likely than Pākehā to be on the receiving end of police force - including OC (pepper) spray, Taser and firearms.

New Zealand police weren’t totally unarmed before the ART trial. Although they describe themselves as a routinely unarmed organisation, officers have access to firearms that are kept in a lockbox in the back of their squad car. There is also the Armed Offenders Squad, armed members of the police called into high-threat situations.

The Armed Response Teams were an offshoot of the existing Armed Offenders squad. The primary difference between these two teams is that Armed Offenders Squad are only deployed at key moments, while the ARTs were consistently patrolling while armed.

What is the justification for the ART trial?

At the announcement of the ART trial in October 2019, then-police Commissioner Mike Bush highlighted the Christchurch terrorist attack as a major reason behind the decision. After the attack, the police raised the national terrorism threat level in our country to medium - where it still remains now.

But Emilie says the trials are not supported by the Muslim community.

“Many Muslim people have told us that they are not happy with the police evoking the memory of the white supremacist terrorist attack in Christchurch to justify putting armed patrols in Māori communities,” Emilie says.

When looking at the statistics of crime generally, Emilie doesn’t think there is any evidential basis for armed patrols in Aotearoa.

In 2017, a Stuff investigation Under Fire found more people had been shot by police in the previous decade than in the 100 years prior. In the decade 2007 to 2017, 35 people were shot, compared to just 42 people shot in the 100 years prior to 2007.

This spike in police shootings could be attributed as a police response to gun violence in the community. But for the past seven years the number of crimes including firearms hasn’t gone up - it has remained stable at under 1% of crime in Aotearoa.

One of the justifications for the trial was that it would keep police officers safer. However, Emilie points out it has been over ten years since an officer was killed on duty. Since 1886, 32 police officers have been killed by criminal acts in New Zealand. 22 of those deaths were caused by firearms - the last of which was Senior Constable Leonard Snee, who was shot and killed by Jan Molenaar in the 2009 Napier Siege. [Update: this article was originally published June 5 2020. On June 19 2020, police officer Constable Matthew Hunt was shot and killed, bringing the number of police officers killed by criminal acts to 33.]

What happened during the Armed Response trial?

The rate of police fatally shooting people has increased. In the past seven months, there have been four fatal shootings by police in New Zealand - however none of them were done by members of an Armed Response Team.

- December 5, 2019: Graeme Sydney Warren, 66, was shot dead by police in Kurow in North Otago after he “held and presented” a firearm at police.

- February 13, 2020: Anthony John Fane, 33, opened fire on a police cruiser in the Bay of Plenty that attempted to stop his car as part of an investigation into a double-homicide in the region. Police returned fire, wounding him. He died at the scene.

- April 20, 2020: Hitesh Lal, 43, was confronted by police in Papatoetoe attempting to enter a strangers home with a machete. Police reported he advanced towards them when they shot him.

- May 19, 2020: Allan Neville Rowe, 54, was reported to be in distress. When police found him in a stationary vehicle, he presented a 22. cutdown rifle. The police say after he refused to drop the weapon multiple times, they shot him.

Despite none of these shootings being from members of an ART, Emilie says this rapid increase of police shootings could be due to the armed response teams normalising the use of firearms as a response tactic, in situations she feels could and should have been deescalated.

“When we normalise the use of firearms as a first response, we normalise the killing of New Zealanders.

“We cannot afford to have a New Zealander shot and killed every two months in this country.”

The ARTs were mostly used for traffic stops

In his announcement of the trial Mike Bush said ARTs would be “focused on responding to events where a significant risk is posed to the public or staff.”

However, police data acquired by Newshub shows that in the six month trial, most armed response teams were involved in routine police work - including over 1400 traffic stops.

An armed response team being called out for low-threat issues at this frequency demonstrates that this trial was more about introducing armed police into routine police work than it was addressing serious crime, Emilie says.

“These trials were called out 70 times more often than the armed offenders squad were. That is a huge amount of contact between armed police and New Zealanders.”

“That might sound justified if there were 75 highly dangerous firearms incidents a day in this country - but that is not the case whatsoever.”

In the trial period, crimes involving firearms made up less than three percent of incidents attended by an ART.

How have these patrolled communities been affected?

At the end of the trial period, the new police commissioner Andrew Coster said in a statement the teams were trialled to support the police's frontline tactical capabilities. “Everything we do, we do to keep New Zealanders safe and feeling safe”.

However, a survey of 1,155 Māori and Pacific people by ActionStation Aotearoa found that 87% of respondents found knowing the police were armed in their community made them feel much less safe, or less safe.

Commissioner Coster said now the trial is over, the Evidence Based Policing Bureau would be reviewing data collected as part of the trial. "Any options that come out of the review will be consulted with communities as part of our efforts to take a collaborative approach to policing.”

But the police’s lack of consultation before starting this trial has been a major point of criticism from Māori leaders and the Arms Down campaigners.

“We were shocked that this happened without any community consultation, and angry that there was no democratic process behind this decision-making,” Emilie says.

Researchers involved in the pre-assessment of the trial identified the importance of consulting with affected communities before starting the trial. Their reports found that there would be a severe impact from the “limited time and ability to consult with Māori, Muslim and other ethnic communities”. Their mitigation recommendation was to have discussions with key community leaders prior to launch.

But in an interview with The Herald, the executive director of the NZ Māori Council Matthew Tukaki said he didn’t know of any Māori leaders who were contacted, and that there had still been no discussion with the Māori Council despite repeated requests.

In response to this lack of consultation, Arms Down campaigners held a hui in late 2019 in the Auckland suburb of Ōtāhuhu, one of the communities that was patrolled under the trial.

Emilie says the hui heard a unanimous call from Māori, Pacific and other minority communities that they do not want armed police on the streets.

“That was a really interesting hui to hold - there were so many stories about people’s experience with armed policing, and racist violence that they have been living with for decades.”

The Arms Down campaign has turned some of their stories into artworks.

Do voters get any say on whether police start carrying guns in New Zealand?

Emilie says they consistently heard from people who feel the police force is totally unaccountable, either to the community - with no consultation on this trial - or to the state.

“Police Minister Stuart Nash and Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern have both claimed that this is an operational decision for the police to make.”

An operational decision is one that the police can make independently - basically, it’s the things police can just choose to start doing something without needing permission from the government.

That’s in comparison to a ministerial decision - something that would need the Minister of Justice, a member of government who’s been elected by the people, to sign off on.

Arms Down campaigners strongly believe the arming of New Zealand police should be an issue that requires decision-making from an elected official, such as the Prime Minister or the Police Minister. Yet, Emilie says their attempts to discuss this with Police Minister Stuart Nash haven’t got a response.

“This is about whether or not police should carry guns in everyday policing. That is obviously policy,” Emilie says.

Professor Robin Palmer, director of clinical legal studies at the University of Canterbury, says it could be argued either way. He says section 16 of the Policing Act 2008 could be interpreted to either mean the decision to initiate this ART trial is an operational decision, or could be the responsibility of the Police Minister.

On one hand, part 1b of this section says “the Commissioner is responsible to the Minister for the general conduct of the Police.”

On the other, 2b of this section says “the Commissioner is not responsible to, and must act independently of, any Minister of the Crown (including any person acting on the instruction of a Minister of the Crown) regarding the enforcement of the law in relation to any individual or group of individuals”.

Professor Palmer thinks the trial of ARTs can be seen as a police operational issue, according to the act.

But, he says, “if the decision is to make a generally armed police force as a rule, I think then it would fall under the responsibility of the Minister as a conduct issue.”

Re: reached out to Minister Nash for an explanation for why the ART trial was an operational issue for the police, rather than something he would have oversight on. He did not answer this question.

Instead staff members from his office referred us to recent remarks he had made, saying that “police make decisions about investigation, enforcement and prosecution independently of the government. Decisions around prosecution must remain at arm’s length from Ministers.”

Where to from here?

Now that the trial has concluded, the police have passed on data collected to the Evidence Based Policing Bureau, who will assess the effectiveness of the trial and the value of these ARTs.

The results are expected at the end of June 2020.

However, there have been concerns over the robustness of the data collected by police on this trial.

In documents obtained by Newshub, a pre-evaluation report from the first week of the trial found the use of survey tools by those involved had been “exceedingly poor”, and that there were a vast range of inconsistencies and discrepancies in the data.

The report also said surveys measuring perceptions of safety had "not been engaged with". "Based upon the data at hand, no valuable insights [could] be attained," the document concluded.

The data collection does not appear to have improved as the trial continued. Documents received by RNZ showed that Armed Response Team officers only properly recorded one in every six callouts they went on - despite being required to record every single callout.

To Emilie and the Arms Down campaigners it is an insult to injury that not only this trial happened without support or consultation from affected communities, but there might not even be any useful data to make valid observations or conclusions from.

“The trial was an abject failure. There was no possible positive that came out of this trial.”

“They put armed police officers on the streets of New Zealand, but they haven’t collected the data to show how that actually went.”

The Arms Down campaigners are committed to seeing this style of routine policing armament rejected in New Zealand. They have created a call-in campaign through their website. The police are also asking for public responses, and are asking for feedback to be emailed directly to them at haveyoursay@police.govt.nz.

Other groups are also protesting against the trial and any ongoing routine police armament, including Māori justice advocates Sir Kim Workman and Julia Whaipooti, who recently filed for an urgent Waitangi Tribunal hearing on the ARTs.

A New Zealand police spokesperson sent the follow response to the issues raised in this article:

NZ police remains a routinely unarmed organisation. The trial of Armed Response Teams ended on 26 April and we are currently undertaking an evaluation looking at a collection of measures including Evidence Based Policing data, and feedback from the public and from our people.

The short trial was approved to explore whether it could improve operational responsiveness, particularly to critical and life threatening incidents, and the safety of both frontline officers and the public.

No officer in any of the Armed Response Teams fired a shot during the trial.

We recognise the ultimate question of the style of policing we adopt needs to reflect a wider conversation across our whole community, balanced with the need to make sure we can keep the public and our people safe. How the public feels is important as we police with consent of the public, and that is a privilege.