Prisoner support network PARS says housing New Zealand’s most vulnerable was difficult before a pandemic. But now, people are being released into a world that’s even more unstable.

Some offenders who were released while the country was in lockdown say they would prefer to be back in prison.

“He just doesn't feel safe back in society,” says Marama Marshall. “Because obviously when he went in, it was so different. And also coming out knowing that there is this pandemic, there is a bit of fear there.”

Marama is a field officer and program facilitator for People at Risk Solutions (PARS). The non-profit organisation provides support and resources to help integrate past offenders into the community.

Marama says one of the hardest things to guarantee ex-prisoners is housing, even without a pandemic. One client of Marama’s who was recently released after three years told her he felt safer in prison. “For him it was a guaranteed three meals a day. This is what a lot of people think about during winter, it is guaranteed meals and shelter as well.”

With a nationwide housing shortage for affordable homes, the average New Zealander can struggle to keep a roof over their head. But finding housing with a criminal record is just that much harder, and offenders who can’t find anywhere to stay are put in emergency shelters.

In 2013 the Department of Corrections estimated between 600 and 700 prisoners were released annually without secure housing.

Corrections national commissioner Rachel Leota confirms this has been the case for some offenders who were released during lockdown. In response to Covid-19, Rachel says Corrections have continued to monitor offenders in emergency accommodation and offer support services, however due to restrictions these are mostly remote. There are regular phone calls and texts and people are given preloaded bank cards to ensure they have access to funds without visiting a bank.

Marama’s team, who serve the Waikato district, worked tirelessly to secure accomodation, food and resources for offenders who were released during lockdown. When Re: last spoke with her, she had organised housing for all ten people who were released in her district, but she said it was a close call for some people. She had spoken to Corrections about emergency shelters and even the possibility of keeping people inside prison because it was safer.

“We needed to make sure we have plans in place because it is hard enough without this crisis. We are pretty much always struggling with accommodation.”

PARS strives to connect people released from prison with whānau, but Marama says finding housing in small towns is particularly challenging. “In the cities it is a bit different because landlords just want a payday. Whereas in a smaller town, that's more of an actual investment. Owners are more picky in smaller towns because everyone talks as well. It's a lot harder on people.”

Towns like Tokoroa are becoming increasingly unaffordable for people relying on benefits to live in. Marama is tasked with the job of not only convincing a landlord to lease to someone with a criminal past, but also to negotiate a reduced rate their benefit can afford.

Ina Pickering, left, says she had no support to find a home when she left prison.

Ina Pickering knows firsthand how challenging reintegration is when you don’t have enough support. She too felt that being on her own in society was more unsettling than staying inside. “Because I knew that when I was in there I was going to be well looked after. It was a safe place to me.”

Ina was in and out of prison seven times for sentences ranging from three months to three years. The vicious cycle highlights how a lack of housing and employment can result in reoffending. “It doesn't help with drug and alcohol addiction because every time I was released back to the community there was no support for me around finding a home, so it was back to my old associates, back to my same old ways.”

When someone is released from prison they are given a Work and Income grant, called Steps to Freedom, of up to $350 to help pay for initial costs. The Ministry of Social Justice says this can be used for “housing, bond or rent in advance, beds and bedding, essential appliances, power, gas or connecting a phone in your home, food, clothing and toiletry items.” But most people living in New Zealand can attest that $350 doesn’t go far for something like a bond. It’s no surprise offenders struggle to make the money last two weeks before any other financial support benefit kicks in.

The way Ina spent her grant shows how quickly insufficient support leads to criminal behaviour. “For me, that money was buying me something to eat. Maybe buying a couple of items of clothing and finding me a bag of drugs that I could turn over. I could have some of the drugs and sell some to make the money back.”

“It is not a very easy stepping stone out of a life of crime.”

For Ina, “there was no staying out”. It is only because of the organisation Reclaim Another Woman (RAW) that her reoffending finally stopped.

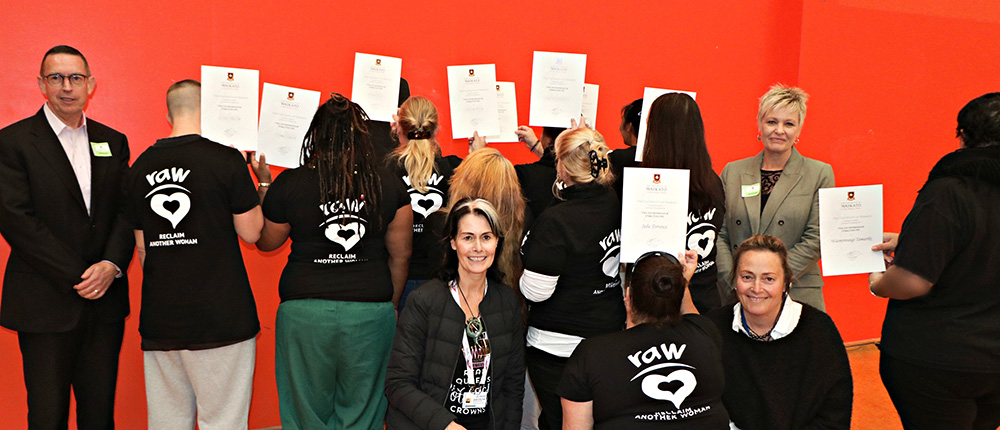

RAW is an independent support program for recidivist women that takes a different approach to rehabilitation. Women are recruited while they are in prison and have access to skill building workshops and training in entrepreneurship. There are about 200 women in the program, but activities are currently limited because prisons are on lockdown.

RAW provides recently-released women a safe place to live and training to help them adjust to life outside.

When the ‘RAW women’ get out of prison they live full time on a remote property in Waikato with eight other women for three months. These early months are the most vulnerable time for new releases, and the women work on skills like parenting and anger management, harvesting and preparing food, exercising, and caring for the property and its animals.

“After the stabilising stage, we start to assist you with accommodation and then we look at whether you want an education, work or connecting back to whānau,” says RAW founder and organiser Annah Stretton. “Once people join RAW, it is for life.”

Despite the restrictions inside prison, Annah says the program is thriving under lockdown. The women are more relaxed with less commitments and financial woes and it has been a smooth transition to remote support. “It's actually better. The Zoom calls have helped us connect with them all together. Trying to get them to travel to a meeting at the same time was chaos. There will absolutely be lots of changes that we make because of this.”

Ina is grateful for the “wrap around support” she received through RAW and says without it, she would be back in prison. “If you go to prison a certain amount of times, they put you in the too hard basket. And some government agencies only support first time offenders. So I felt like I was left with no support. But they didn't give up on us,” she says.

Ina has now been out of prison for five years. She’s living independently with two of her children and studying to be a barber. “I love my life at the moment. Everything seems to be working out fine. It is just about making time for my babies.”

Marama says now more than ever people need to be open minded to the prospect of housing those with criminal pasts. She says it will make communities safer, and research overwhelmingly shows stable housing reduces recidivist behaviour significantly, especially with violent offenders.

“I get that everyone who has offended is going to be criticised but at the end of the day, society needs to stop dictating and judging. If you want a low-offending area, we need to house and employ the people who offend.”