By Anna Harcourt and Todd Henry

It might seem strange in 2019 to write an article about cross-cultural relationships. But even today, many of us still partner up within our own culture.

In fact, 95% of people who identify as Pākehā marry someone else who is Pākehā. 81% of Asian New Zealanders marry other Asian New Zealanders and 73% of Pasifika people marry other Pasifika people.

But as Aotearoa becomes more multicultural, marriages between different ethnicities are becoming increasingly common. It’s harder to generalise about what a typical Pasifika family is or what a Pākehā household looks like.

As part of our series Rediscovering Aotearoa: a decolonisation series, we filmed a short documentary on the kaupapa of Aroha | Love, with a young couple in Ōtautahi (Christchurch). Tyla Harrison-Hunt is Māori from Ngāi Tahu and Saba Khan-Hunt was born in Pakistan and moved to Aotearoa when she was eight.

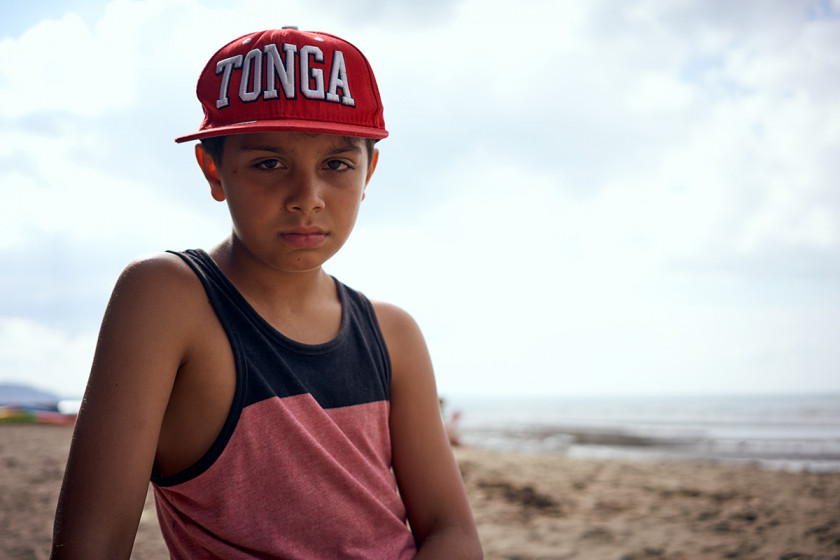

As an accompaniment to this short documentary, we asked photographer Todd Henry to create a photo essay about his own cross-cultural family. Todd lives in Tāmaki Makaurau (Auckland) with his wife ‘Anau Mesui-Henry and their kids Ngata and ‘Ileini.

Todd and 'Anau

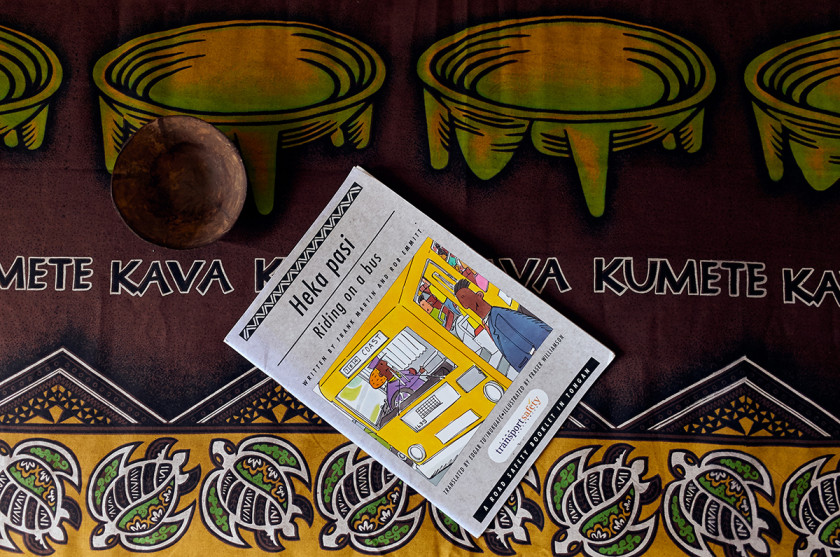

‘Anau was born in Longolongo, Tongatapu in Tonga and moved to Auckland with her family when she was four.

Todd was born in Delaware in the United States, and grew up in a tiny farm town in Pennsylvania.

They met at a barbeque in a friend’s backyard in Auckland in 2008 when Todd was over on a working holiday visa. “I was like, I think this guy is looking at me,” laughs ‘Anau. She decided to test him out and walk to the other side of the lawn to see if he followed.

“I ended up standing next to her, and the first thing I asked her was if she was Samoan, but I was wrong, she’s Tongan,” says Todd. “She didn’t really take offence but she did correct me.”

In the eleven years since, they’ve gotten married, had two kids and moved country multiple times. At the start, neither of them thought being in a cross-cultural relationship would be a huge deal.

“I didn’t think like, ‘ooh I better brace myself for differences’,” says Todd. “I thought, I’m open-minded, I understand that what’s normal for one isn’t normal for others. But there definitely were times I was like, what the heck?”

For ‘Anau, those differences came to light when they moved to the States to be closer to Todd’s parents when their son was five months old.

“Everyone thought I was Mexican,” laughs ‘Anau. “I thought, are they going to tell me to go back to the border or something?”

“The part of the East Coast [of the U.S.A] I’m from is very monocultural, it’s mostly white people,” says Todd. “The first time I heard of Tonga I was 13 in Earth Sciences class and the teacher was talking about the Tonga Trench.”

In fact, in Delaware, the state where Todd was born, it was actually illegal for a white person to marry a black person until 1967. “Growing up there were hardly any intercultural relationships,” he says.

'Anau, Todd and their kids Ngata and ‘Ileini

For ‘Anau, all sorts of things were different in the States. Take the sense of humour, for example. “I definitely missed having Polynesians, that laughter and humour. As a Tongan we can laugh about anything or everything, we laugh at our failures, we laugh at our achievements. The humour was different in the part of America we lived, it had to make sense.”

The big farm in sleepy small-town Pennsylvania was a world away from home in Mangere East. “It was everything I didn’t grow up with, animals, horses, a lot of cooking and baking,” she says.

And people had different priorities in life. No one would visit during the week because they wanted to focus on work the next day. “People would only make time to socialise in the weekends,” ‘Anau says. “It was a bit boring.”

They moved back to Auckland in 2013. For Todd, he wasn’t used to how communal Tongan life is.

“Tongan families are very close, there’s always people around. I kid around about it by saying ‘Tongans can never do anything alone’.”

That was one of the things they argued about when they first got together. ‘Anau would want Todd to come with her on every trip to the supermarket, whereas he expected her to go alone.

“She’d be like, ‘you have to come with me’, and I’d be in the middle of something and I’d be a little bit frustrated like, why?”

But Todd realised he grew up in a household where his parents spent a lot of time doing things individually. “But the way ‘Anau grew up her parents were never separated, they always did everything together. Her dad would never just jump in the car and go to the supermarket by himself.”

While he at first found it frustrating, Todd’s come to realise it’s just a cultural difference. And he’s found it leads to a greater sense of community. “You never get lonely. I guess I’m just used to it now, I’ve come to the point I prefer having people around.”

It feels like people have your back, Todd says, like they’re all part of your family. “When you marry a Tongan, that family will treat you as Tongan even if you’re not.” If he meets a stranger who’s Tongan, as soon as he tells them his wife is Tongan it changes the whole dynamic.

“And that’s really special to me. I grew up in Pennsylvania, and I’ve married into this culture from the other side of the world and they don’t treat me as an outsider.”

There aren’t many cultural similarities between Tonga and America, ‘Anau says. But as individuals they have the same values. “We care about similar things like the environment, animals, and we really value people. We do care for people that others might not take a second look at, or groups that are easy to be judged, like deportees, or people who might be struggling,” she says.

For ‘Anau, being Tongan is something she just is - “it’s not something I ever sit down and think about whether I fit in or not.”

“But in terms of the social constructs and makeup of society of Tonga, there’s definitely stuff I’m different in. I enjoy getting tattoos, and in my conservative traditional family women don’t get tattoos. I have a lot of guy friends, and that’s different because in my family women hang out with women, and men hang out with men.”

“Within our cultures we were both different,” says Todd. “I grew up in a small town and people don’t leave that place, whereas I went to New Zealand for no reason. I never really fit in my hometown, but in Auckland there were all these people from other cultures and I felt like I fit in.”

In some parts of the States intercultural relationships drive people crazy, says Todd. “But here there are people from all different backgrounds having kids, and it’s normal for their kids to have multiple worldviews.”

The most recent census data shows the number of people who identify with more than one ethnic group is growing - up from 9 per cent in 2001 to 11.2 per cent in 2013.

And nearly a quarter of Kiwi children identify with more than one ethnicity. That number is increasing, up from 19.7 per cent in 2006.

“My kids see things from an American and Tongan and Kiwi perspective,” Todd says. “Here, transcending different cultures is the norm.”

This article is a part of our series Rediscovering Aotearoa: a decolonisation series. Watch our short documentary on Aroha | Love here and listen to our podcast here.

Made with support from NZ on Air.