By Kahu Kutia

For many, Te Wiki o Te Reo Māori comes with difficult questions around our dreams for this language. Kahu Kutia writes about what the future holds, and what te reo for everyone might really mean.

We all have our own relationship to Te Reo Māori.

For some, that relationship is a life-long friendship. Te Reo Māori has been your constant familiar since birth, and a path that leads you deeper into te ao Māori every day.

For others, Te Reo Māori might be the tūpuna hanging on the wall in your lounge that you never met, that you know nothing about.

We all come to te reo Māori in a different way. I think of my own relationship to te reo, its own ebbs and flows.

Present at birth, lost in the mainstream schooling system, and reclaimed again because I had the privilege of access to a tertiary education. Something that is absolutely not a reality for everyone.

I think of my own pāpā, who was beaten for speaking. I’m aware of the intergenerational impact this has on me. He very rarely spoke te reo to me, out of the perspective given to him in colonial violence that this language wasn’t useful for a modern world. I internalised these feelings for myself for a really long time.

Growing pains for te ao Māori and wider Aotearoa

I feel so lucky to have a relationship with te reo Māori. But I also know what it feels like to be disconnected from this reo. And so in my own perspective I wonder who is currently missing from the picture of reo revitalisation, and what mahi is yet to be done.

Maybe your relationship to Te Reo Māori is joyous and one of celebration. Maybe Te Reo makes you want to bolt the doors and hide away. Maybe you just have no idea how to feel about it at all.

For tangata whenua, when we understand the complex colonial history and how colonisation continues to impact us today, we can only come to the conclusion that all of these feelings are valid and important to acknowledge. We’re at a really interesting point in the growth of te ao Māori. In some ways it feels like our culture has never been stronger, but we’re also in danger of leaving some of our people behind.

We face growing pains too as we inevitably head into an increasingly bicultural world and as Pākehā and tauiwi connect more to our language and culture. Yeah, we hate that ‘bicultural’ word. But the conversation around it is inevitable.

I think these growing pains are complex, and sometimes there might not be a clear right answer.

We must learn to navigate as best we can, guided through conversations that stem from relationship and deep whakapapa. We must hold space where nuanced criticisms and validly painful experiences are held alongside deep visioning for growth and for more for te iwi Māori.

Even to dream for our reo is a privilege - not accessible to those who can only focus on what they need to survive each day or week. There is a lot of collective mamae and it's crucial that we hold it well if we are to make any progress forward.

We face these really important questions, and Te Wiki o te Reo Māori is one of a number of times throughout the year when these questions are reflected back to us in a way that doesnt always feel safe and good.

Te Wiki o te Reo Māori and a mixed bag of feelings

It often feels tokenistic more than anything else. Because those of us in te ao Māori are always thinking about this stuff eh? Always doing the work.

I’ve done the eye rolls plenty of times. At the people using te reo Māori for just one week of the year. At the many instances I’ve been called on to provide free cultural consultation for people who don’t even want to understand the wider structural issues.

Within myself and only for myself I’ve held space for that, alongside a desire to celebrate all of the things Te Wiki o te Reo Māori has to celebrate. That’s where I’ve been at all week.

Te Wiki o te Reo Māori was born in a time in Aotearoa that was very different. When Te Reo wasn’t heard ever in the mainstream media or among the wider public. A time when it wasn’t used by random businesses and organisations as a virtue signalling tool and when our language was still considered to be dying.

This week comes around and the questions which those of us within te ao Māori are always asking bubble forward into more mainstream circles of conversation.

What do we want for te reo Māori? What do we want for te ao Māori? Just as we all have our own relationship to te reo Māori, I think we all also have our own answers to those questions too.

Moving forward and looking at the past

Our history is patched with many reminders that Te Reo Māori was not lost, it was actively taken away from us. Our people have never been passive, but resistant and resilient. Sometimes resilience means time and energy to fight and to organise, and sometimes it means getting through the day and putting bread on the table.

Our history is a reminder of where we have come from, the trajectory that our world is on, and of the ways that others have fought for the world we currently have for us.

There’s policies like the 1867 Native Schools Act or the 1907 Tohunga Suppression Act that had a detrimental impact on mātauranga Māori and te reo Māori - designed specifically to assimilate Māori into Pākehā society and teach entirely in English.

There’s the land wars, instigated by Crown agents, a massive drain on our people and culture. There’s the influence of Pākehā diseases we had never encountered, and the loss of knowledge holders. There's World Wars, and the urban assimilation of our people through pepper-potting policies, and Christianity, and constant widespread systematic racism.

Our reo came close to loss, and was lost to many. But never entirely faded away.

In the second half of the 20th century, the Māori Renaissance emerged. In the renaissance, we can mention things like Ngā Tamatoa, the Māori Language Society and the launching of the Māori Language system.

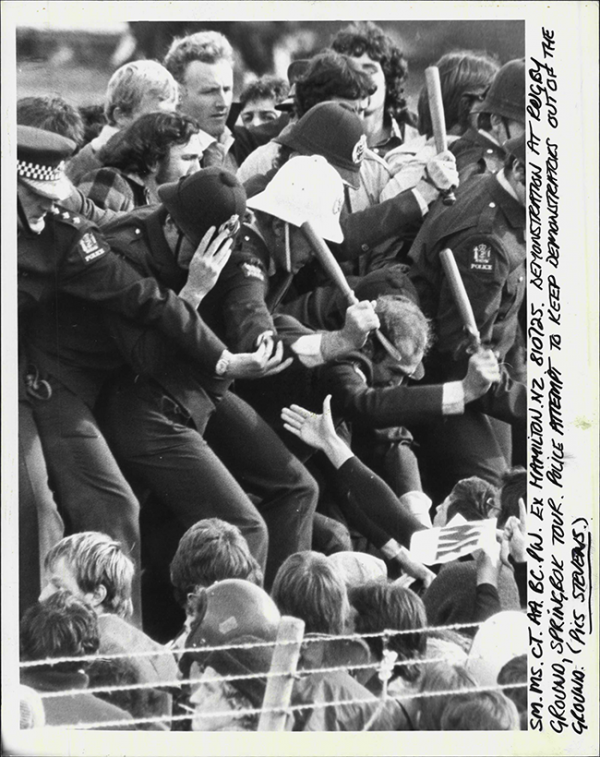

We can mention movements like Te Matakite o Aotearoa and other connected land rights movements. We can connect the Kōhanga Reo movement, and the WAI11 Treaty Claim, as well as events like Springbok Tour protests denouncing wider systems of racism and white supremacy.

As someone who was raised post-renaissance, I think I have often taken so much of what we have today for granted. I remember my own shock when learning about the story of Naida Glavish or Hinewehi Mohi. The idea that there was a time where saying Kia ora at work or singing the national anthem in Te Reo was actively frowned upon.

Do we want a bilingual Aotearoa? What questions should we ask before that?

When we talk about future aspirations for te reo Māori, one of the big questions to come up is a bilingual Aotearoa. Something that many within te ao Māori have been fighting for for decades.

But even the mere idea of it comes with so many sticky questions. Not just how do we achieve a bilingual Aotearoa, but should we?

What would this even look like? How would Pākehā and tauiwi meet te reo Māori, and how do we ensure that the mauri of te reo still sits firmly with Māori, and by that I mean all Māori.

This week has been a painful reminder that these are not easily solvable questions, and that there’s a long way to go before we can even hold space and facilitate a good process of wānanga amongst ourselves as Māori.

For those of you who spend most of your waking days thinking about how frustrating this world is, how violent colonisation has been for our people, and how overwhelming this all is, maybe you will relate to this feeling I have now which is just to freeze.

Sometimes the complex layers of oppression pile up like a million blankets and it feels impossible to even move one of them. Inevitably I come back to our wellbeing as a people, and our ability to live meaningful, considered lives.

But it’s overwhelming because I think that the vitality and the revival of te reo Māori is connected to Māori health outcomes, and Māori access to housing, and Māori figures of employment, and our ability to access Māori spaces.

I get caught in the endlessly spiralling koru of the world and it’s problems and I just end up feeling like that meme of the guy from It’s Always Sunny in Philadelphia, explaining his in-depth conspiracy.

Everything is connected!!! Nothing is ever as simple as cause - effect - solution.

Rebuilding the whare for our own people first

What do we want for te reo Māori? What do I want for te reo Māori?

I want growth and experimentation and new words and ways of speaking te reo that speak to a language able to grow and adapt with its speakers. I want us to have productive conversations that open the space of karakia and karanga and whaikōrero to more of our people, so that our traditions will live on.

I want te reo Māori to be accessible to all Māori who want to learn it. I want far greater resourcing for Te Reo Māori education. I want more work done to remove structural barriers that create burnout and exhaustion in Māori educators. I want reo learning and reo resources that work for all learning styles and requirements.

I want irrelevant racist men with no understanding of our language to not have a platform to share their ignorance.

I want rangatahi raised today to have no experience of the criticism and trauma and challenges that our pakeke faced in their own reo learning and upbringing. I want our learning of te reo Māori to be deep and rich and woven with the history of how we came to where we are today.

I want te reo for everyone in Aotearoa too, but I want te reo for our own people first.

We’ll only win when everyone is on the waka

Te Reo Māori can and should continue to grow, championed and pushed by our pou reo who spend everyday thinking and strategising for the revitalisation.

Championed as well by the person saying their pepeha for the first time, and the person memorising the basics. Championed by the parents raising Māori children, and the people working full-time jobs to care for their families, and the people spending hours trawling for their whakapapa and the long lines of Māori waiting for access to reo education from institutions without enough resourcing to offer te reo Māori to us all right now.

As a kōhanga reo child, as a current speaker of te reo, just as a Māori person I am so grateful and so proud of my relationship with te reo Māori. But until te reo Māori is something accessible to all Māori, we have not won.

I love the trajectory that te reo Māori is taking, I just want to make sure that we bring everyone on the waka. I think, maybe more than any practical goal or percentage, or specific deliverable, that’s what I want for te reo Māori.

More stories:

‘I don’t want rangatahi to have to fight for our reo’: 6 people on their hopes for te reo Māori

‘Nau mai te rekareka’: We’ve got some sexy reo Māori for you

‘You’re not going to get a job in te reo Māori’: 3 people who proved this wrong