This story is part of a series on sex work in Aotearoa to support the release of Red Light Boys.

Read our other piece on the history of sex work in Aotearoa.

Content warning: This article discusses police violence and underage sex work.

It’s nearly 8:30 am and Kay’La Riarn is hurriedly packing her bag before school.

At 14, she is already nearly six foot tall, thanks to her “part Māori, part Viking” ancestry.

Stashed at the bottom of her bag are a crop top and a pair of jeans that are so tight, an imprint of the stitching is left behind on her skin after she takes them off.

She likes those jeans because they make her long and slim legs look even longer.

Kay’La’s biggest asset, her legs. Photo: Renati Waaka

Kay’La leaves the house, but instead of going to school, she walks all the way to Porirua town centre to meet up with older men.

She finds a bathroom to get changed, replacing the tight ensemble in her bag with her school uniform.

Kay’La walks around and gets picked up by men in their 20s or 30s.

They go for a drive before parking up and having sex. She learns quickly what the men like - blow jobs mostly.

Because of her height, Kay’La says she looks 18, so the fact she is underage never comes up. They don’t ask, she doesn’t say.

This was more than 40 years ago. Looking back on her life, Kay’La says she didn’t realise what she was doing at 14, was sex work.

“I was an adventurous type so I found it exciting. I enjoyed the sex with them,” she says.

“They would give me money after we had sex but I thought that was just money for the bus to get back home. It wasn’t until I moved to Wellington and started working on the street that I realised what I was doing with them was actually sex work.”

While this story is about Kay’La’s personal experience, we want to make it clear it is illegal for anyone to pay someone under the age of 18 for sex.

If you are under the age of 18, you are not breaking the law if you are in sex work. However, brothel operators, clients and even friends or workers aged 18 or over can be fined or imprisoned for facilitating people under the age of 18 into sex work.

Kay’La is a trans wahine sex worker now living in Te Whanganui-a-Tara. Her home in Aro Valley is not far from the red light district where she established herself as a sex worker - and where she is still connected today.

Kay’La’s long and colourful career is a legacy of whakawāhine sex workers.

“Whakawahine means ‘as like a woman’,” she says.

“They say it's a choice [to be trans] and that, but no, you’re just born this way. We all found each other and stuck together because we all knew this.”

Who are the whakawāhine sex workers?

Since before sex work was decriminalised in New Zealand in 2003, whakawāhine sex workers worked on the street. This was mainly because back then, trans sex workers were not allowed to work elsewhere.

When sex work was illegal, cis-gendered sex workers would pretend to be ‘masseuses’ and would work in ‘massage parlours’ that were really brothels operating in secret.

Kay’La says trans Māori sex workers were excluded from these spaces by the massage parlour operators so they were left to work on the streets.

“It was well known - trans [people] do not work in parlours, full stop,” she says.

“The only reason I got to work in one was because I was friends with someone who owned one and they asked me to pop in every now and then when a client requested a trans sex worker.”

Working on the street was more dangerous than working in parlours because you were more visible to the police. Working on your own meant you had to gauge whether a client was safe or know how to escape if they weren’t.

These working conditions meant whakawāhine sex workers across the country connected for support, guidance, and company.

This bond lives on even though many have left the streets to work in now legal brothels, overseas or online for themselves.

I didn’t find the whakawāhine, they found me

Tiana was first scouted by her whakawahine “drag mother” on a busy netball court in Wellington.

Tiana is her working name - she wanted to remain anonymous in this story for privacy reasons.

Back then, Tiana was 18 and just starting to transition.

Growing up in the suburbs of Porirua, she wasn’t aware of hormone replacement therapy or surgery to become a wahine. She was naive and happy, plucking her eyebrows, shaving her legs, and “running around as a crossdresser”.

Kay’La’s favourite dress to wear. Photo: Renati Waaka

“[My drag mother] came up to me and said ‘you’ve got potential, come see me’ and gave me an address,” Tiana says.

That day was the start of Tiana being tucked under her drag mother's wing and being guided on not only how to be a sex worker, but a wahine too.

“She made us learn how to love ourselves and be happy with ourselves just the way we were,” Tiana says.

“She taught me, ‘it's not the hormones that make the woman, it's the attitude.’ She changed my way of thinking.”

A whakawahine in training

Tiana’s drag mother was known to everyone as Mushroom.

“Because she was the first whakawahine to have the mushroom bowl cut,” Tiana laughs.

Mushroom would train Tiana and other sisters on the tricks of the trade.

One evening they met at a shopping centre and waited to get picked up by a man so they could learn an important lesson: how to not be fooled by a man’s flattery.

Newbie Tiana came back after seeing a client and was over the moon because he made her feel beautiful.

“But Mushroom would say to me: 'That's just men, you’re going to be in love with the next man too, that’s what they do.’”

“It was a good lesson to learn because once I started working the rori (street) there were a lot of men who tried to win us over with flattery instead of paying us,” Tiana laughs.

“She was auditioning us, preparing us for the streets.”

I still remember the night I met Kay’La

Tiana not only remembers the moment she first met Kay’La in the 1990s, she also recalls exactly what she wore that night.

Down a long stairwell in a boarding house in Wellington, Mushroom ushered the new girls down a narrow hallway. On the left was Mushroom’s friend’s room, and on the right was Kay’La’s room.

Mushroom wanted her “drag daughters” to meet and connect with other whakawāhine before they went out and worked on the streets.

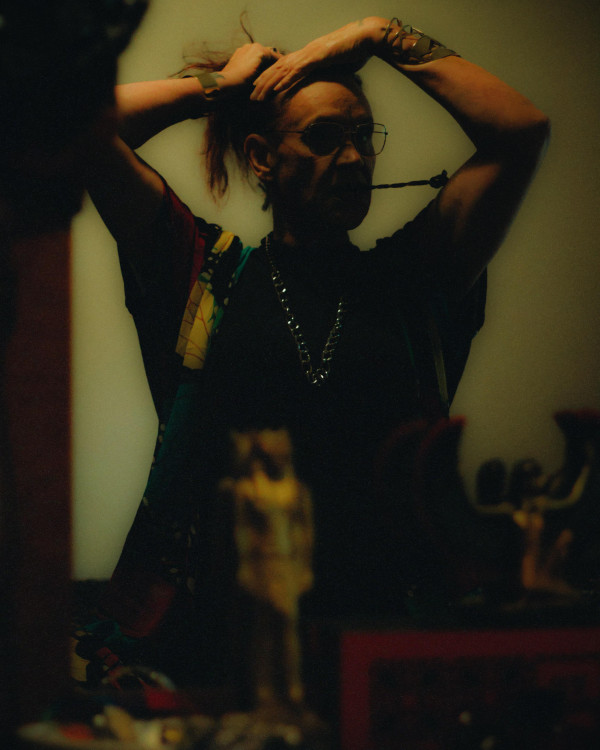

Kay’La putting on lipstick in the mirror. Photo: Renati Waaka

Sixteen-year-old Tiana stared up at Kay’La in awe as she put on her make-up.

Her hair was long and thick with her fringe swept to one side. She wore long silver earrings that caught the light and a cross over top that “showed off the girls”.

“Because it was all about the business, we had to advertise,” Tiana laughs.

“I even remember the shoes she wore, stilettos with one strap around the ankle and two around her feet. I was amazed.”

Kay’La's favourite pair of shoes. Photo: Renati Waaka

Growing up in the suburbs of Porirua, Tiana says she had never seen such glamour.

“It was like a movie, I felt, you know, ‘I’m going to play with the big girls now.’”

Te whakawāhine o Te Whanganui-a-Tara

Kay’La and Tiana spent a lot of their career working in Wellington with a community of whakawāhine.

Sometimes it didn’t even feel like work.

“We had a coffee shop we would all go to and clients would know they could meet us there,” Kay’La says. “It was one big social life.”

Whakawāhine became such an integral part of Wellington’s nightlife, shopkeepers would be grateful for their presence.

“They got to really like us because we were there at night and we would hear robbers and violence on the streets,” Kay’La says

“We would walk around in circles around the block and our presence there would be a deterrent for anyone who wanted to do something stupid.”

Kay’La says cafes would give them free coffee in the morning and thanked them for watching out for their stores.

The whakawāhine would have movie nights and shared BBQs and go out drinking in nightclubs after they had made enough to pay their bills.

“Even if society rejected us, it didn’t matter. We had our own society,” Kay’La says.

Tiana agrees.

“I felt like I belonged. It helped me live as a whakawāhine, a lady with a difference.”

Police treatment of sex workers wasn’t equal

Newspaper clippings from when sex work was illegal detail the horrific abuse some sex workers experienced at the hands of their clients.

Some were brutally beaten, raped, and murdered. There were stories of sex workers being dragged behind cars and held at knifepoint.

This was something Kay’La had to be wary of. But at that time, she says she was more afraid of the police than of clients.

“One day I was waiting to meet another sex worker down at the wharf in Auckland and the police asked me why I was there. I told them I was meeting a friend and went to turn around and walk away. The next minute I was in the water trying to climb out.

“That’s what the police could do, they just picked you up and threw you in the water.”

Kay’La says a friend of hers was picked up in a police car and told they were going back to the station. But instead, she was dropped off at the airport and stripped down to her underwear.

“The police thought it was a big laugh. When she made her way back to town the girls took her off the street and took her home and took care of her.

“But we couldn't complain because if we did it was called plausible deniability, it's an old trick.”

Many sex workers like Kay’La were too afraid to go to the police when they were assaulted by clients or officers for fear they would be arrested instead.

Kay’La says on multiple occasions she was hit with a phone book while she was in police cells, “because it didn’t leave any marks on your body. They would make you strip down and spray [you] with water hoses and humiliate you”.

Kay’La says police would also call them the ‘F’ word and other derogatory names.

“They would call us our birth gender and dead names, they would do it quite loudly too.”

A dead name is the birth name of a trans person who has changed their name as part of their gender transition.

Police would take photos of whakawāhine and hang these inside police stations, Kay’La says.

“They would share photos around so when they went on their raids around the street, they knew who they were looking for.”

Whakawāhine bore the brunt of sex work policing

The Crimes Act 1961 prohibited brothel-keeping and living off earnings made from sex work - but these laws were not applied equally.

Māori sex workers were arrested at three times the rate of European sex workers.

From 1997 to 2000, Māori sex workers made up over half of all soliciting convictions.

During this time ‘men’ made up 54% of these convictions, however, these sex workers were mostly trans Māori women misidentified by the police as ‘men’.

The pattern of these convictions also shows there was a deliberate focus on policing street-based sex work more than indoor sex workers.

Kay’La’s bed in her Aro Valley flat. Photo: Renati Waaka

When Re: News reached out to police about these allegations, a spokesperson told us: “Police cannot comment on these specific allegations in the absence of an investigation, following receipt of a complaint.

“Police currently work closely with the Aotearoa New Zealand Sex Workers' Collective at a number of levels to help address sexual violence and sexual exploitation.”

The relationship between whakawāhine and police today

On a cold night in Wellington, a man bounds up to Tiana when she is working and asks where to score drugs.

No matter how many times Tiana says no, he keeps pestering her.

“Look hun, can you see a sign on my head that says ‘drug dealer’? I thought I had ‘whore’ written on my head,” she laughs.

When the man continues to harass Tiana, she threatens to call the police.

“They won’t care, they have more important things to worry about,” the man snarls.

Tiana calls the police and within five minutes they arrive and tell the man to leave because he is making it hard for Tiana to get clients.

“From days where there was no police assistance to having police respond to your call just like that - a lot has changed since sex work was decriminalised,” she says.

Before the law changed, the police were the last people Kay’La would go for help. Now, she and Tiana help train police on how to respectfully interact with trans and rainbow sex workers.

A University of Otago review on the impact of decriminalisation revealed 64% of sex workers found it easier to refuse clients, and 57% said police attitudes to sex workers changed for the better.

Research has found Māori street-based sex workers in particular now feel more able to reach out to the police for help.

Kay’La says this is the case when sex workers have been assaulted or when they need help getting money back from a client who refused to pay.

Whakawāhine street-based sex workers have also worked with police to negotiate when patrol cars should visit street venues, to not scare the workers’ potential clients away and make sex work more difficult for them.

“Since the law change, we’ve been able to progress and grow education and trust. We are a lot more visible these days, not only as sex workers but as trans,” Kay’La says.

“If someone turns around and says ‘you're a sex worker’ I say ‘yeah I am, actually’. And they can't do nothing about it.”

Photos by Renati Waaka

Where to get help:

- 1737: The nationwide, 24/7 mental health support line. Call or text 1737 to speak to a trained counsellor.

- Suicide Crisis Line: Free call 0508 TAUTOKO or 0508 828 865. Nationwide 24/7 support line operated by experienced counsellors with advanced suicide prevention training.

- Youthline: Free call 0800 376 633, free text 234. Nationwide service focused on supporting young people.

OUTLine NZ: Freephone 0800 OUTLINE (0800 688 5463). National service that helps LGBTIQ+ New Zealanders access support, information and a sense of community.

This story is part of our series of work on sex work in New Zealand. You can watch the Red Light Boys series here.

Turning sex work into a career | Red Light Boys

“No money is worth your health. Particularly in this job. Your body is your business.”

A Porirua porn star on why she switched from finance to sex work

“Last year, I turned over just over $200,000, solely from sex work.”

Good strip club etiquette means you tip

Strippers tell us how you can get the most out of a fun night at a club.