If you’ve ever been caught short you may have popped into the local dairy to grab a few essentials – toothbrush, toothpaste, maybe a bit of soap – but a jar of skin whitening cream? Maybe not.

In the Philippines however, next to the soap, for the equivalent of NZD$4 you would find any number of skin-whitening products all telling you one thing – you are not enough.

On a trip back to the Philippines, 20 years after his family migrated to New Zealand, Filipino Kiwi comedian James Roque noticed an obsession he felt was toxic to Filipino’s sense of identity.

“The Philippines has one of the largest industries when it comes to skin whitening and I think that speaks to the extent of the issue in the whole country,” says James.

In his show Boy Mestizo, which returns to Auckland this week, James unpacks the uncomfortable legacy colonisation has left on his homeland as hoards of young Filipinos try to meet beauty standards set historically by Spanish and American class systems, believing it will create better opportunities for them.

“If you think about it at a base level, the Spaniards came (in 1565) and lived there for 300 years and had their own standards of beauty being like ‘if you’re Spanish, you’re more beautiful,” says James.

“The Spaniards handed us off after the Spanish-American War (in 1898) and the Americans got a hold of our education system and kept their own standards of beauty and the preferred language – which was English – and put that into the schools.

“I think if you mix all those things up, the combination of all those things is what we have today.”

Research shows more than a third of Filipino women regularly attempt to alter their skin tone with lightening creams. But, isn’t that comparable to our westernised self-tanning habits?

“Yes and no”, says James. “Yes in that at the very base level it is still people being unhappy with their skin colour and wanting to change it.

“No, it’s not exactly the same because how many times have you not been able to get a seat on the bus because you weren’t tanned enough? Never.

“In the Philippines that is such a genuine thing because your skin colour is attached to who you are and where you stand in society.”

In New Zealand, James’ Filipino complexion is admired. He has a sought-after summer tan and he doesn’t burn as easily as others.

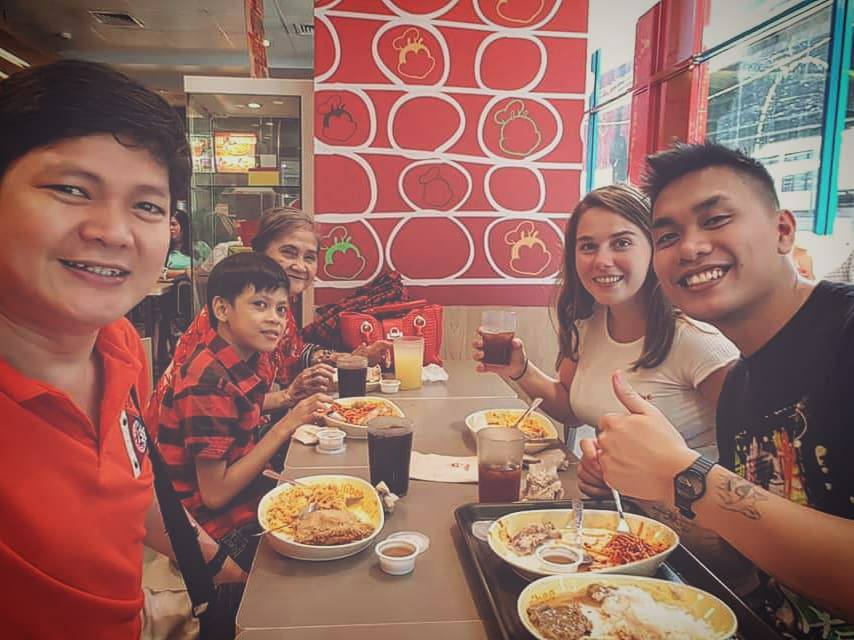

But while in the Philippines he saw how people with lighter skin were treated differently in Filipino culture.

“I went back to the Philippines with my white partner. In certain areas we got special treatment because she was a Westerner – that I didn’t get when I was by myself and that really messed with me for a while.”

In colonised countries, a lighter complexion signified being from a higher class because you were less likely to be outside in the sun doing hard manual labour or you were related to some of the more powerful western colonisers.

James recalls the desirability of a light complexion being instilled in him from early childhood.

“I mean I still get it now – things like ‘don’t play in the sun because your skin will get darker and no one really questions what effect that has on a kid, you know.”

James was also taught, that pinching your nose before going to bed should be as ritualistic as brushing your teeth – so your nose was as pointy as a Westerner and you didn’t turn out “ugly”, of course.

After reading about this same ritual in a book by Filipino author and journalist Alex Tizon and confirming with his Filipino friends that they’d experienced it too, James realised it was time to unpack the baggage he’d carried with him from his homeland.

“I couldn’t keep reading. I put the book down and I actually cried” says James.

And, at this years’ NZ International Comedy festival, James turned those tears of generational trauma into tears of laughter when he debuted Boy Mestizo, inspired by the faux pas of his trip back to the Philippines.

“A word like Mestizo (which is used to describe someone of mixed race with a lighter skin complexion) is just thrown around… synonymous with the word attractive,” he says.

James is quick to point out that even though the subject matter is heavy, the show is just as silly and nonsensical as you would expect.

“I think comedy is the easiest way to really get people to listen to what you’re trying to say because if you disarm them by making them laugh first, build a rapport with them, then they’re more likely to actually absorb or take in what you’re trying to say”

Though the country may still be wrestling with internalised complexities about beauty and its relationship to society, Filipinos have a history of overcoming.

After being colonised first by the Spaniards, then by the Americans and occupied by the Japanese during WWII, the country stands independent.

“I‘ve always admired the resilience and the strength of Filipinos,” says James. “The indigenous people have dealt with and been through so much trauma in the history of the entire nation that I always find it a source of strength and source of pride for me.”

Boy Mestizo is James’ display of resiliency, a push back against what has been accepted in the past.

“What the voice of the show is trying to do is trying to empower young Filipinos to change the way they think about the norms and question things.”

Boy Mestizo is showing at Basement Theatre on October 1 - 5.