Growing up, assimilation meant acceptance for Tommie Love.

As a queer African boy living in Pōneke/Wellington, Tommie felt he not only had to assimilate to his parent’s Tigrayan culture, but also to mainstream Western society.

“Assimilation meant being somewhat invisible, because being who I was meant more attention,” says Tommie, now 22.

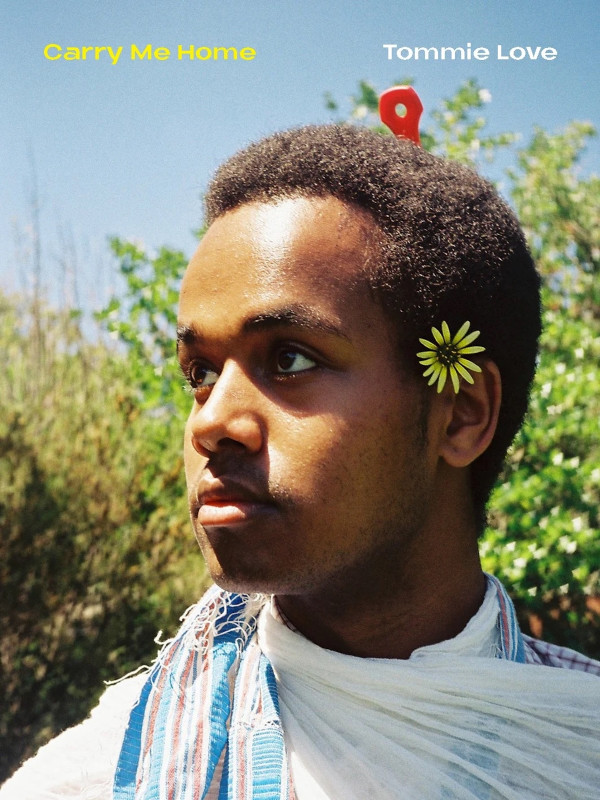

Tommie Love. Photo: Carry Me Home

“You have to exchange your culture and your heritage and your language to have assimilation, which a lot of African parents encourage.

“Once I assimilated, it meant acceptance. It meant being tolerated. It meant being non-threatening. It meant I could just breathe and be another kid.”

Carry Me Home is a new photo book written by Tommie Love.

The book explores Tommie’s journey growing up queer and African in Pōneke/Wellington, as well as his parents’ experience immigrating to Aotearoa.

Carry Me Home cover.

‘A way to honour my full story’

Tommie says Carry Me Home makes him feel as though he’s being accurately seen.

“I don't like how a lot of Kiwis who grew up with African heritage aren’t really acknowledged for their upbringings and them being a part of the fabric of New Zealand,” he says.

“So I wanted to apply those elements into the book in a way to honour my full story.”

When Tommie was 11, he visited his motherland – Tigray, Ethiopia.

It was the first time he was in a place where everyone looked like him.

“When we went on the Ethiopian Airlines flight from Dubai to Addis Ababa, everyone on the flight looked like us.

“It was pretty funny seeing all the diasporic communities from the UK, Sweden, America and every other place, just in this plane going to Ethiopia. I had never experienced that before.”

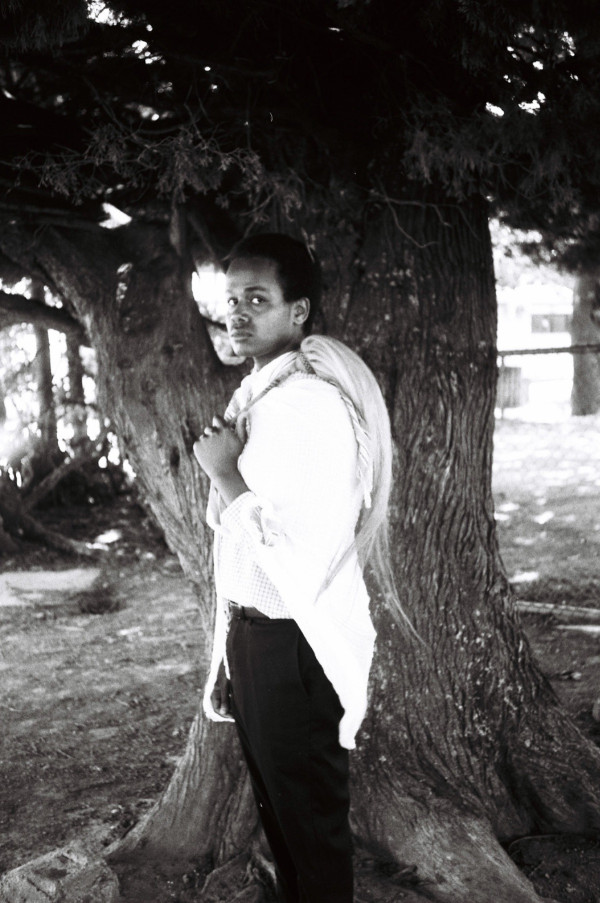

Photo from Tommie Love’s debut book, Carry Me Home.

When he arrived in Tigray, he was able to meet family and engage in his culture.

“It was a dope experience. I feel like I felt more like myself.”

Accepting your heritage doesn’t mean accepting everything

“When I came back to New Zealand, I felt a lot more confident. Because I thought, ‘you really can't tell me anything about me, because I got to experience what being in my culture is like’,” Tommie says.

“I felt strong. I felt very strong.”

Tommie says he was able to accept his heritage, he also had to accept that he didn’t have to accept everything.

In Ethiopia, same-sex sexual activity is illegal.

“I don't have to accept the customs, [such as the homophobic attitudes in Ethiopia], that inherently make me invisible.”

After writing Carry Me Home, Tommie says that he feels empowered taking space.

“I feel like it's really cool to take space. It's so that people who are younger than me, or going through those experiences of feeling insecure in their blackness or Africanness, in context to being gay or lesbian or trans, [are able] to have that duality.

“I feel like sometimes society can make it so that you don't take space. And I think that's for everyone. Tall poppy syndrome is such a bad thing that we have here.”

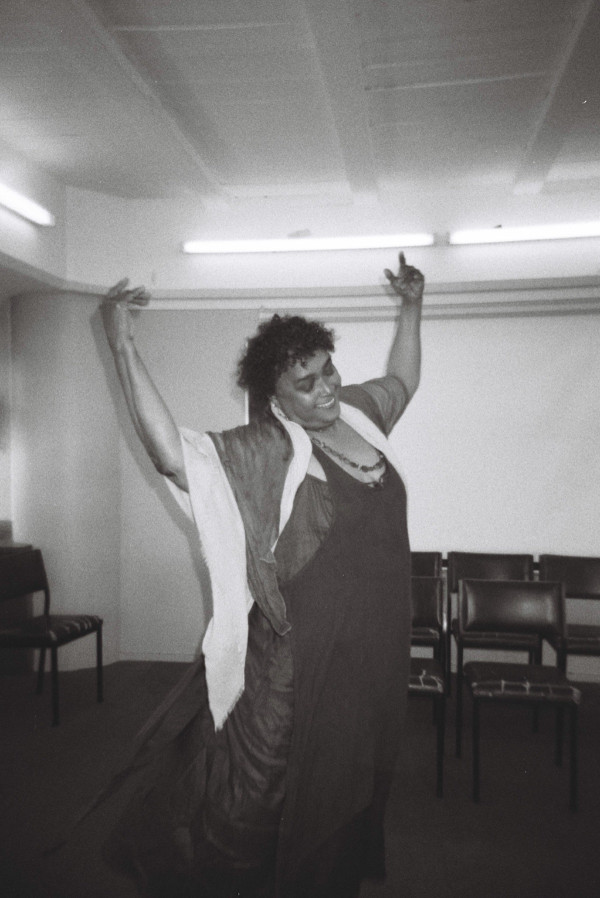

Photo from Tommie Love’s debut book, Carry Me Home.

Bridging people together

Tommie hopes there’s something for everyone in Carry Me Home.

“This is a New Zealand story, but also a migrant story. This is a story that can resonate with the siloed experiences, but also could be a story that can resonate with someone who is indigenous, or someone that is Asian or someone that's European.

“I wanted to break those barriers and tell stories that can really bridge people together.”

More stories:

When your South Asian identity and queer identity don't feel compatible

"It’s still painful for me to revisit, because it was something that was supposed to be precious.”

We made a series about the good parts of being queer

For the past 12 months we’ve been working. Working hard so we can please you.

Lesbian Master Doc: A PDF helping women realise their sexuality

Sherry Zhang explores how this resource has helped people think more deeply about their sexuality.