On the evening of Tuesday August 25, Wellington watched as a local icon burnt down - the anarchist house at 128 Abel Smith Street.

Located right beside the Terrace Tunnel entrance to the motorway, it had become famous - infamous to some - for the striking banners it would hang with messages against war and wealth inequality, in support of Māori rights and gender minorities, and many other causes across the past twenty years.

“The history of the house is fraught,” says Katrina Tamaira, who lived in 128 Abel Smith from 2003 to 2004. “If it was a person, it would be a flawed character.”

“But it symbolised a lot. The history of resistance in New Zealand. The passion and idealism of the brighter futures imagined there. And also, the lost potential and disappointment when it didn’t achieve that.”

Here’s a visual history of the iconic building, along with ten things you might not know about its history.

The front of 128 Abel Smith Street - 7 August, 2005. Credit: Andrew Ross

It started as a maternity hospital

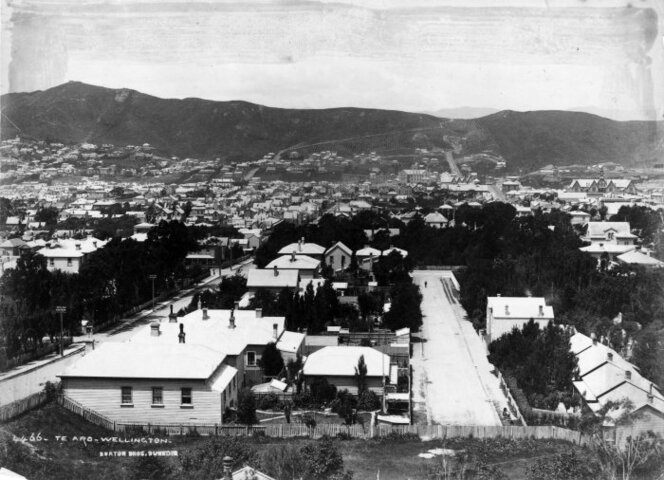

Southeast view over Te Aro, Wellington 1880’s. Abel Smith is the street on the left, and 128 would eventually be built at the far end of the tree line that can be seen on the street. Te Aro, Wellington. Ref: PAColl-5671-40. Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington, New Zealand.

Before 128 Abel Smith Street was the birthplace of ideas, it was the birthplace of babies. Built in 1898, it was turned into a maternity hospital in 1911, and remained so until 1945 when medical expectations shifted towards the built-for-purpose medical facilities we use now.

The longest-lasting maternity business in the building was Waimarie Private Obstetrics - Waimarie being Te Reo for lucky - which was a thriving business, with 186 patients in 1936.

Four nurses who are thought to be associated with the maternity hospital in 128 Abel Smith Street. Harris, Esme Enid, 1913-1993: Photographs. Ref: PA1-q-115-10-6. Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington, New Zealand.

It became a home for Wellington’s Lebanese community

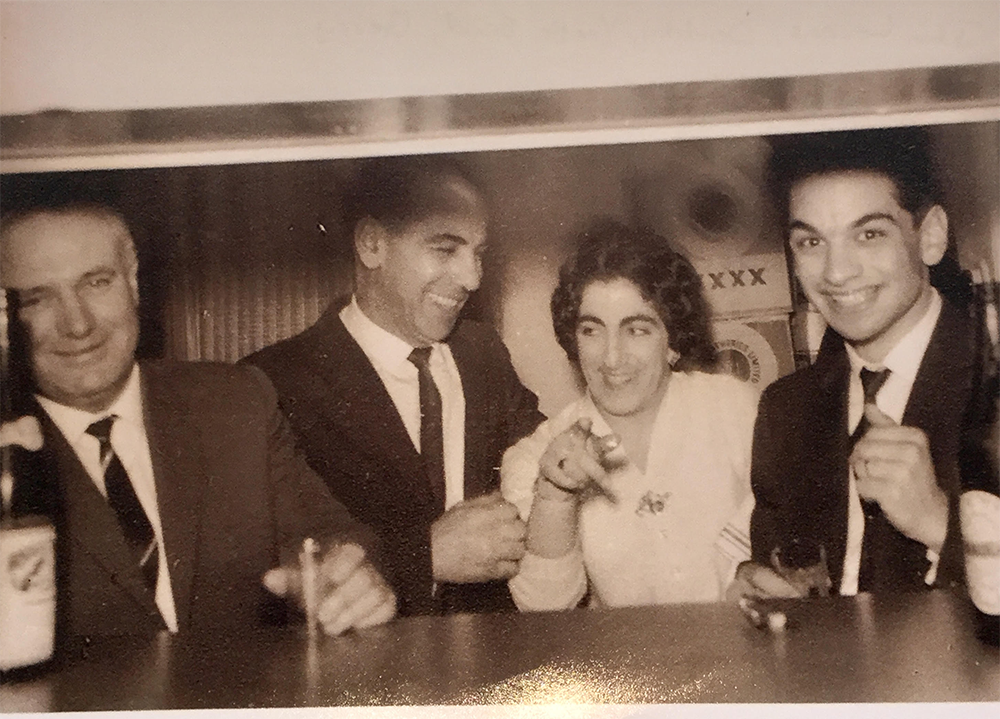

A Wellington Lebansese Community Gathering in the 1960s at 128 Abel Smith Street. From left to right - John Levens, Albert (Fred) Peters, Yvette Sood and Jerry Peters.

In the late 19th and early 20th century, there was a period of heavy migration from Lebanon as the country’s population grew and social and political tensions deepened in the region. After several decades of success in New Zealand, in the 1940s a group of first-generation migrants and their children formed The Lebanese Society of New Zealand. The society went on to purchase 128 Abel Smith Street in 1957 and used it as the social hub of the Wellington Lebanese community until the 1980s.

They equipped it with a range of amenities - including billiards rooms, a dance room, and a backgammon hall. It was often where visiting Lebanese people would stay, and also became the space for significant events in the community, such as wedding receptions and parties.

Current Lebanese Society committee member Serena Moran says 128 was described in this period as “majestic and beautiful”

However, as the founding members of the Lebanese society grew old and engagement with the society declined over the 1980s and 90s, the Lebanese community’s engagement with 128 also dwindled. As a result, the house had fallen into disrepair by the early 2000s.

Its anarchist roots began with a protest against a motorway extension

Bypass protest poster on a building on upper Willis Street - 10 October, 2004. Credit: Nick Lloyd

Perhaps unsurprisingly, 128 Abel Smith Street became one of New Zealand’s most prominent activist spaces with a protest - this time, against a road through the heart of Wellington that was announced in 2001.

This road, now called the Wellington Inner City Bypass, required the demolition or relocation of heritage buildings and disruption of what was the heart of Wellington bohemian culture around upper Cuba Street. As a result, its proposal caused a six-year protest from hundreds of Wellingtonians and led to the inception of many anti-bypass groups.

Construction of the entrance to the motorway as part of the Wellington Bypass. The back of 128 Abel Smith Street can be seen in the centre of the frame, behind the trussing, and to the right of the orange tree - June 9, 2005. Credit: Nick Lloyd

It had been stripped bare, so anti-bypass community groups worked to restore it

Emily Bailey and Kerryn Pollock tending to the Tonks Avenue community garden - 2001

Around 2003, having identified that 128 Abel Smith Street was unoccupied and in dire need of repair, some anti-bypass groups took it upon themselves to tidy it up.

“All of the wall linings had been ripped out, there was no electricity, no doors,” says Kerryn Pollock, who was part of the anti-bypass movement. “It had been totally pillaged for anything of value - every piece of copper had been ripped out - and there was no handrail on the stairs, which was a total hazard.”

“The toilets were completely blocked, and there was no running water - so someone had to volunteer to unblock the toilets,” Kerryn says. “I remember a guy rushing through the house towards the skip out front holding a literal bag of shit.”

“The grand vision was to somehow fundraise to restore the house, and show what the community could do with these kinds of buildings rather than demolishing them for a road.”

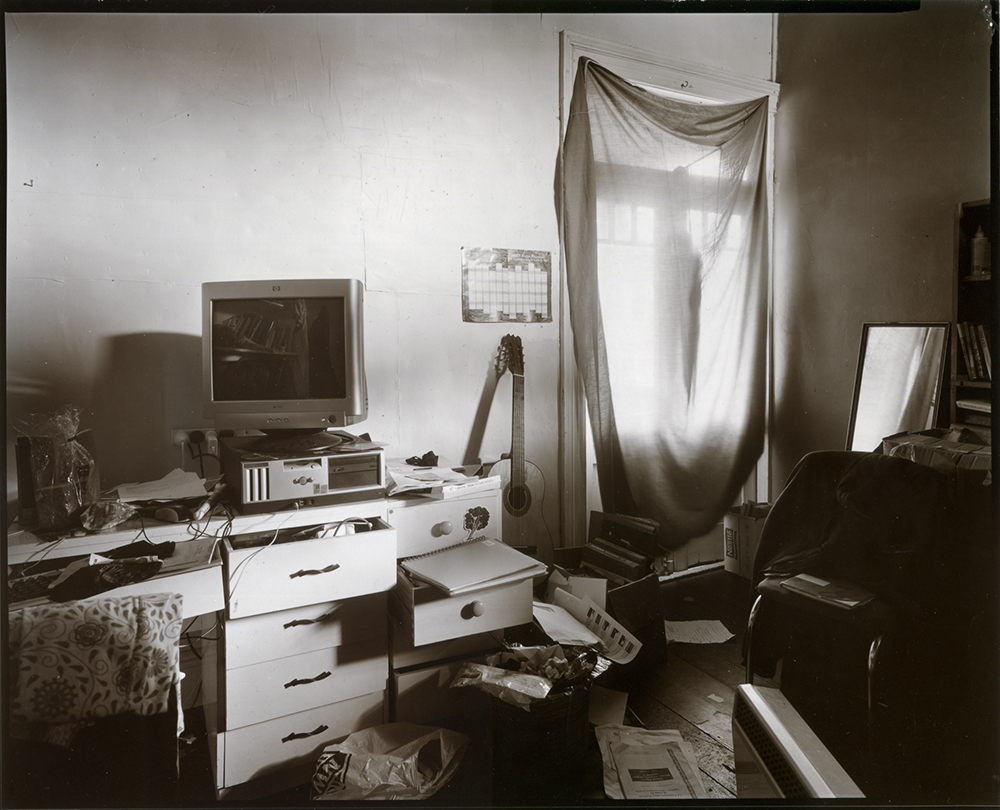

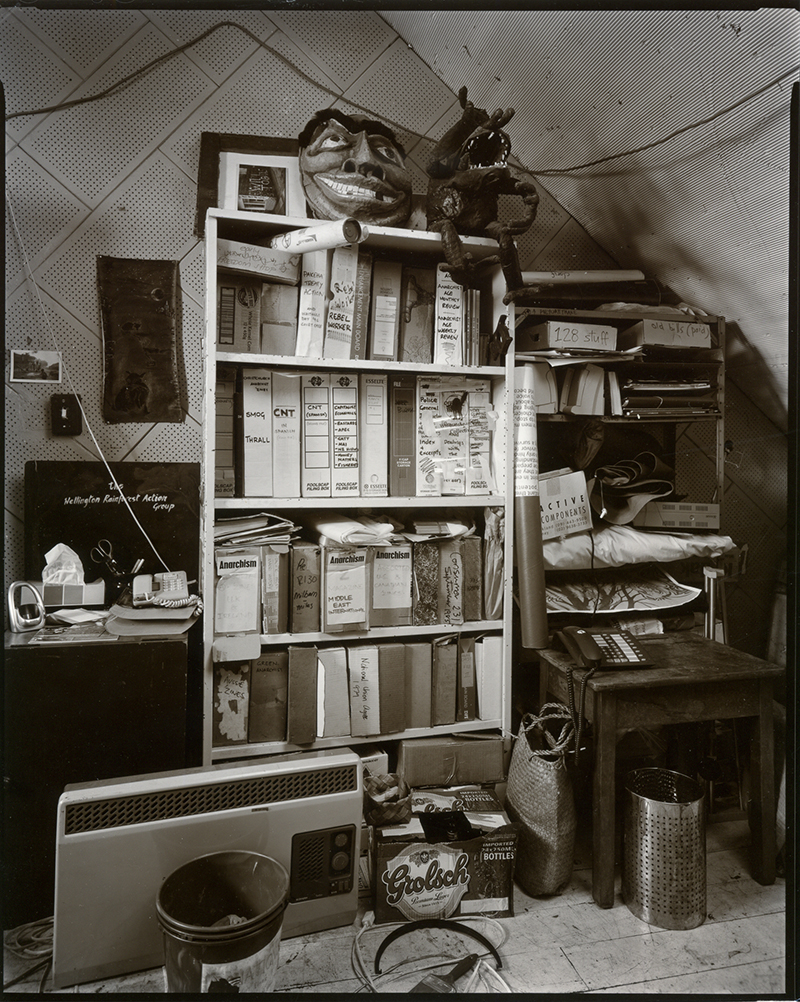

Caretaker Sam Buchanan’s room in 128 Abel Smith Street - 03 August, 2007. Credit: Andrew Ross

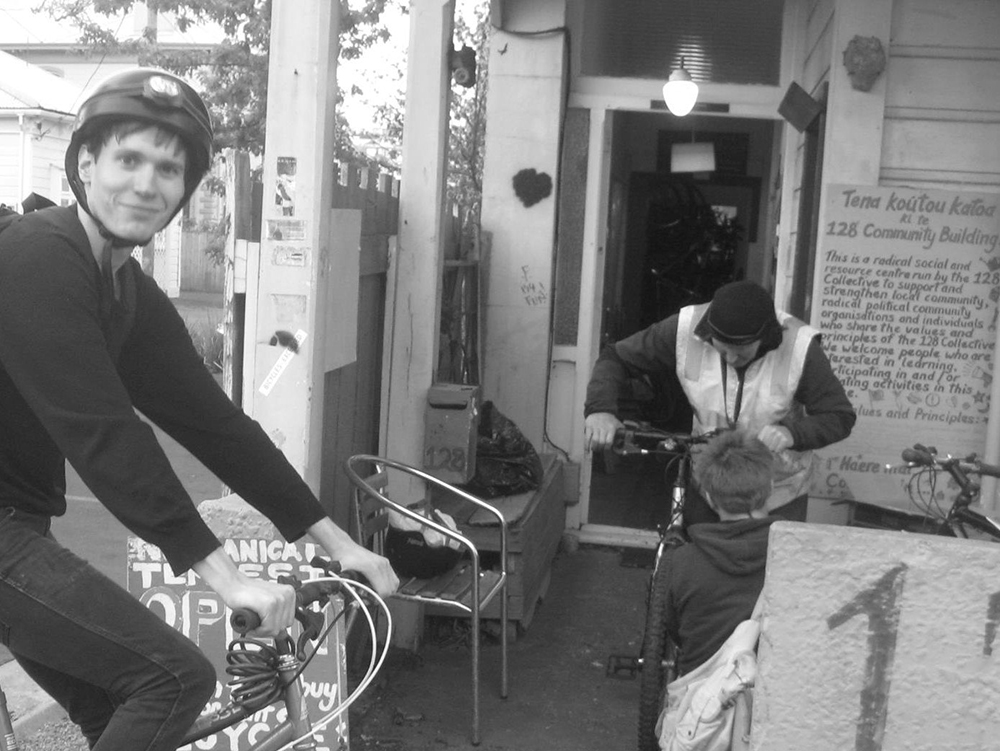

Anarchist squatters turned it into a (semi) livable home and bicycle repair workshop

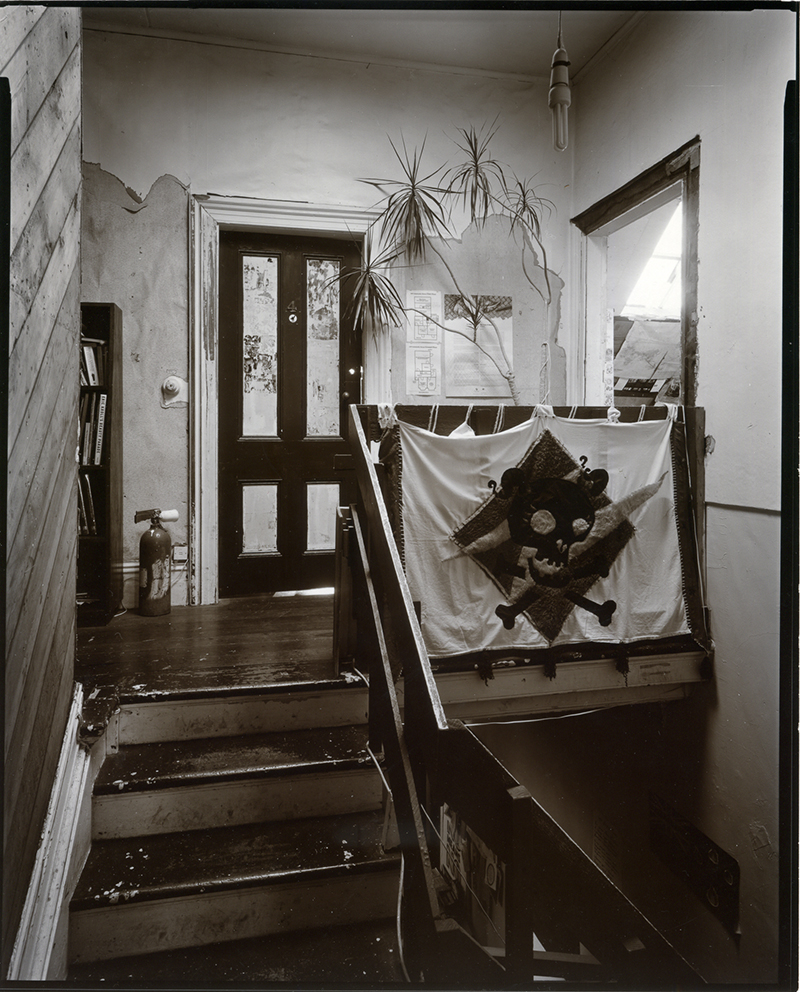

128 Abel Smith Street stairwell - 28 August, 2007

A subset of the bypass protesters were part of Wellington’s anarchist community.

Having worked to restore 128 to a - somewhat - livable state, members of this community decided they would squat there. The building still had no power or running water at this stage.

This was the birth of 128 as the anarchist house, and anarchists would continue to have a deep connection to the building throughout the next two decades.

The most prominent fixture of this was the community bike repair organisation Mechanical Tempest, who would run free workshops where anyone could gain the skills, tools and parts necessary to repair their bicycle.

Stephen Parallel and other Mechanical Tempest members working on bikes - 2013

It became Wellington’s home of protests

Katrina Tamaira protesting the destruction of a building on Oak Park Avenue by shackling herself to it - 14 January, 2005

Throughout 2003, it became clear that this squatting arrangement wasn’t sustainable. It was decided by the community - the core of which had started calling themselves the 128 Collective - that a formal arrangement needed to be made about who was living in the house, and what the expectations were.

This was also when the house started to become a more official hub for social movements beyond the bypass protest. They allocated rooms in the house for meetings, and a booking system for different groups to allocate time there.

“But it wasn’t all boring political meetings,” says Katrina. “There were also gigs, with our open-mic night Rusty Tongues, film nights, presentations from visiting activists, pot lucks.”

If I Had a Gun playing in the Blue Room as part of the Pink Tie Incident Gig - a fundraiser for an activist's legal costs after he was sued for damages for wiping his dirty hands on a US Marine's pink tie at a protest against the Iraq War - April 17, 2004. Credit: Bell Murphy

It was raided by police as part of the Urewera raids

Police removing evidence from 128 Abel Smith Street as part of the Te Urewera terror raids - October 15, 2007

At 6am on Monday October 15, 2007, a series of raids were simultaneously conducted by police in Te Urewera and across the country, in relation to the Terrorism Suppression Act. 17 people were arrested in relation to allegations that Māori rights activists had been conducting paramilitary-style training camps.

In the end, none of the 17 people arrested were charged under the Terrorism Suppression Act because the Solicitor General said the evidence was insufficient. Four people were found guilty of illegally possessing firearms.

128 Abel Smith Street was one of several buildings raided in Wellington. Nobody was arrested from the house, but a large number of documents and clothing were confiscated.

In 2013 the Independent Police Conduct Authority found the police acted unlawfully.

A collection of files - mostly meeting minutes - at 128 Abel Smith Street, only months before the raid - 28 May, 2007

Conflict arose from clashing ideologies

128 Abel Smith Street with a banner protesting against the sale of New Zealand assets to international buyers - 27 April, 2013. Credit: Dylan Owen Collection, Alexander Turnbull Library

With so many different groups, ideologies and causes occupying the house, it was inevitable some conflict would arise.

“As people started asserting their politics and positions on the house - that is when the cracks started to form and chasms started opening up,” Katrina says.

An example of this was a confrontation that happened at the 10-year anniversary of the radical left centre at 128.

As part of this celebration, the collective put out a call to have anyone and everyone involved with the house come together for a celebration - with music, presentations, and a potluck dinner.

A boil-up was brought along by some Māori activists that had been involved with the house during the height of its Māori rights movements.

At that time, there was a very strong vegan ethos within the house. So much so, that in an act of protest one of these activists removed the boil-up from the table and placed it on the ground.

This breach of tikanga led to a massive and ugly confrontation in the midst of the party. It left the collective wondering how they were going to balance the wide array of ideologies and priorities of those involved in the house now, in the past, and into the future.

It became one of Wellington’s safe spaces for gender diverse people

Gender Minorities Aotearoa organisers Ahi Wi-Hongi and Hiromi Yagashita amongst clothes donated to the Gender Minorities Aotearoa’s charity shop, Aunty Dana’s Op-Shop - 2018. Credit: Yuval Zalk-Neale

What followed was a decade from 2009-2019 that could be described as ‘the safe space’ period.

One of the keen focusses of the house in this time was building out a reference guide on how to maintain safe, respectful and inclusive discourse in the house among so many different groups and perspectives.

In this period, organisations such as Gender Minorities Aotearoa thrived within 128, acting as a drop-in centre to help trans people with issues such as documentation and healthcare. As part of their presence at 128, they opened Aunty Dana’s Op-shop, a clothes store that helped fund their operations.

Gender Minorities Aotearoa has grown into a national organisation that has become a key part of the education, outreach and community for takatāpui, trans, and intersex people in New Zealand.

Gender Minorities Aotearoa organisers Ahi Wi-Hongi (second from left), and Hiromi Yagashita (far right) with visiting activists - 2018

A fiery end

The side of 128 Abel Smith Street the morning after the fire - 26 August, 2020. Credit: Supplied by WCC

Finally, after 17 years in the space, with the Lebanese Society having reformed, the radical social centre’s tenancy in 128 Abel Smith Street came to an end in September of 2019. Fortunately, Gender Minorities Aotearoa were able to find a new space on Riddiford Street in Wellington to establish their new headquarters, along with bike repair group Mechanical Tempest.

Up until the fire, the Lebanese society had been considering if and how they would renovate 128 Abel Smith Street.

It was during this time that squatters once again took residence in the house.

Lebanese society committee member Serena Moran says during the first Covid lockdown, the group had been unable to regularly visit the house, and so they had a neighbour keep an eye on the building.

In the last two weeks, the neighbours began reporting that there had been a group of men coming and going from the house.

“We went in only the weekend before the fire and found evidence of people living there - with clothes spread around everywhere and even some weapons - like a tomahawk,” Serena says.

“We had turned the power off also because we were worried about fire, and so there were candles everywhere. Which is probably actually what caused the fire in the end - turning the bloody power off, which led to them lighting candles.”

The society cleared everything out of the house, took it to the police, and made a report. They then secured the house, and boarded up the windows.

Only a few days later, the house burnt down.

Once the fire had been quelled, the Police and Fire Department decided that the house was unsafe to enter. As a result, no investigation could be made to determine where the fire started or the cause.

Fire and Emergency says no investigation is ongoing. Police say they will have no further involvement, but that if anyone has information pertaining to the fire they should contact 105.

“All we know is that there were people seen running from the building [around the time of the fire],” Serena says. “I suppose we can choose to connect that or not.”

“There is also the question of whether it might have been done deliberately - perhaps because we boarded it up to keep them out - or whether they were just in there with a candle that started the fire accidentally.”

“But, we don’t know.”

Firefighters survey 128 Abel Smith Street the day after the fire - 26 August, 2020. Credit: Supplied by WCC

While the Lebanese society and those involved with the radical social centre are mourning the loss of this historic building, Katrina has found solace in the fact that her time associated with the building had taught her that it’s ultimately not about the space at all, but what was done within it.

“Activism happens all the time, everywhere. You don’t have to live in a house with other activists. You can do simple things, like writing a policy at work that, for example, ensures transgender people are acknowledged,” Katrina says.

“It’s minor, but you can do activism in small ways in different parts of your life and it grows into big things.”

A more comprehensive version of this history can be found on the 128 Radical Social Centre website.

Andrew Ross’s photography was contributed courtesy of the artist and with assistance from James Gilberd of Photospace Gallery.