By Kahu Kutia

Before moving to the city Kahu Kutia typically thought of Māori in the city as disconnected. But she learned that for some Māori, the city is the reason they are able to be their most authentic selves. Today’s episode of He Kākano Ahau, ‘Decolonising sexuality and gender in Wellington city’, is a double issue. Check out the video here and podcast at the bottom of this article.

Kahu Kutia joins in with Tīwhanawhana kapa haka.

In the making of He Kākano Ahau, I found myself in a small meeting room at Victoria University with Kevin Haunui. Kevin was working on his Phd in takatāpui wellbeing. The term takatāpui today describes a person who is Māori and who exists somewhere on the wide spectrum of gender and sexual identity. Like any other term, takatāpui should not just be applied to any of your queer and Māori loved ones. Rather it is a korowai that a person may choose to take on to bind their rainbow identity to the whakapapa that underpins all of us as Māori. After all, whakapapa is usually the first building block of our identity for us who are Māori.

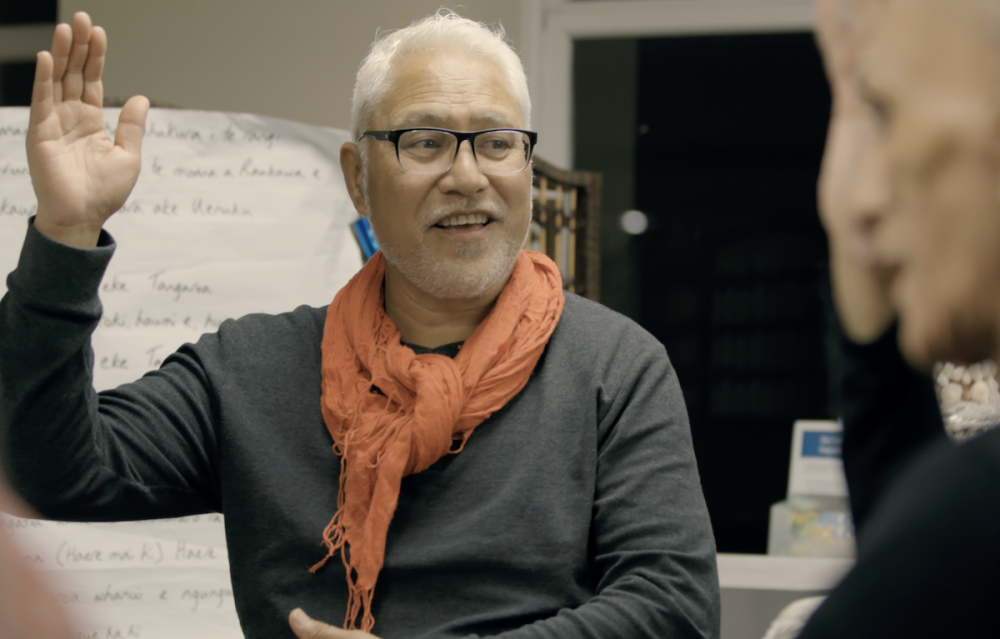

Kevin Haunui, takatāpui academic and kaiwhakahaere of Tīwhanawhana kapa haka group.

Kevin is also one of the kaiwhakahaere of Tīwhanawhana, an urban hang out space for takatāpui and friends to spend time together and practice kapa haka. Over a cup of tea we talked about some of his research, and the motivations behind creating the Tīwhanawhana space. We talked about the necessity of providing spaces that cater to a takatāpui worldview.

Mainstream LGBTQIA+ spaces can still be spaces that harbour racism and white supremacy, and heteronormatism and the gender binary is still strong in some of our traditional Māori spaces. Where then, do takatāpui get to be their whole and complete selves?

One of my favourite things about te reo is the layered learnings that come from really looking at some of our kupu. Kevin talked about the word Māori. A quick Google search reveals the following definition of māori (with a lower case):

1. (modifier) normal, usual, natural, common, ordinary.

I like to imagine the first tipuna to be asked what they are shrugging their shoulders in confusion. What do you mean? I am normal, I am me. Because to define ourselves as Māori had never existed before the arrival of the coloniser. Our identities had been woven in whakapapa, in hapū and iwi histories. So to me that means the boundaries of being “Māori” are limitless. My mind is blown when Kevin says to me: To be Māori is to be everything you could possibly be.

Ariki Brightwell features in Episode 3 of He Kākano Ahau. Photo Dianna Thomson.

I think of all those in my life who are on the forefront of decolonisation work. The vast majority are takatāpui and queer and trans and they are Māori. I think of the kids figuring out for themselves where they want to be on the marae. The kids flipping on Ru Paul with indigenous realness. The kids loving someone they’re not supposed to. The kids born in to a pā already rich with takatāpui love. I think of the work of amazing creatives from across Te Moana Nui a Kiwa to create spaces like Tīwhanawhana, FAFSWAG, Coven, Filth AKL. There is no dismantling colonisation without challenging the norms we inherited from Christian missionaries, the toxic hegemony of man and woman in monogamous marriage forever and ever. It’s a worldview that is not only incorrect, tbh it is boring.

Maybe one of the most destructive effects of colonisation is the way it renders takatāpui unseen. You can exist, but we won’t talk about you, won’t tell the stories that have tīpuna who are like you. It’s an invisibility that has erased takatāpuitanga from the stories we inherit in te ao tūturu Māori. One of the only ones to be generally known is the story of Tūtānekai and his male lover, it’s this story that the word takatāpui was harvested from. It’s an invisibility that means takatāpui will generally only have a background role on the marae.

Kayla Riarn and Kahu Kutia on the streets of central Wellington. Photo Dianna Thomson.

In Te Whanganui-a-Tara, there is a history that is only just beginning to be celebrated. In this city I also met up with Kayla Riarn to learn some of her history of the central city. I won’t tell her story here, it’s in episode three of He Kākano Ahau and our series video. But Kayla told me stories about Wellington city that I’d never heard before. Abel Smith, Cuba, Marion, Ghuznee. All iconic streets to any person who has ever lived in Wellington, and for the first time I saw how they housed the legacy that led to the creative and liberal city that we think of today.

The place that was a shop corner to me became the place that Kayla worked for many years. The street I’d wandered down on many blurry student nights became the place where in the 70s and 80s, Kayla met so many of her friends. She was a baby queen under the wing of Wellington’s premiere royal, Carmen Rupe. It was trans Māori drag queens who build the bones of the city I now call home.

The history of takatāpuitanga is long, and rich and wide as the ocean we call home. And it is takatāpui who push the boundaries of what we consider to be Māori today. In making episode three of He Kākano Ahau, I learnt that the city can be a powerful papakāinga for takatāpui. If we can address a whole history of inequities, the future for our babies might be bright.

He Kākano Ahau is a podcast written, researched, and hosted by Ngāi Tūhoe writer and activist Kahu Kutia. Kahu lives in Wellington after spending the first 18 years of her life in the valleys of her papakāinga, Te Urewera.

Over six episodes, Kahu explores stories of Māori in the city, weaving together strands of connection. At the base is a hunch that not all of us who live in the city are disconnected from te ao Māori.

Listen to episode three below, and watch the video here.

He Kākano Ahau is produced for RNZ by Ursula Grace Productions, made possible by the RNZ/NZ On Air Innovation Fund.

![]()